Share

https://int-magazine.com/interview/fellow-travellers-chris-wright/

クリップボードにコピーしました

Interview #8 2025.10.13

Humans, by nature, are storytellers.

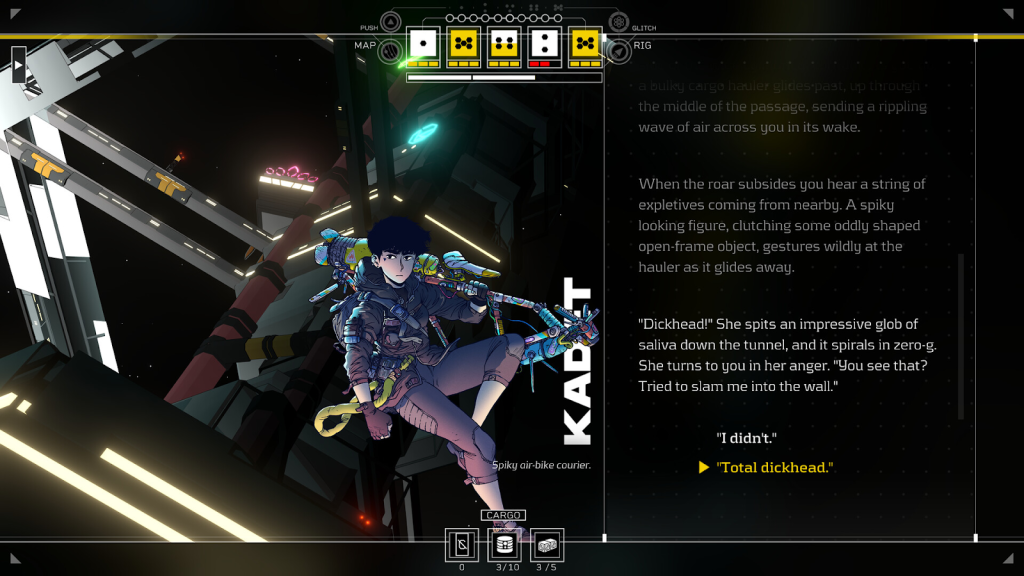

But telling stories for a living is a different matter altogether.Fellow Traveller is an Australia-based publishing studio that prides itself on “exploring the possibility space of what narrative games can be.” With titles such as Citizen Sleeper, Paradise Killer, Genesis Noir, No Longer Home, Orwell, and 1000xResist under their belt, anyone who is a fan of a good story would do well to keep the publisher on their radar.

(Titles published by Fellow Traveller)

By going against the preconceived notion that artistic games cannot survive in the current market, Fellow Traveller has been steadily putting out hit after hit, thereby increasing its reputation in the narrative indie game scene.

But how does a small-scale publisher survive in the games industry’s stormy seas? We sat down with Chris Wright, founder and CEO of Fellow Traveller, and asked him about his publishing philosophy and how he manages the studio’s activities, from market strategies to building relationships with developers and game communities.

Planning & Interviewer / Daichi Saito

Editor / Jini

Author / Shu Chiba

Photographer / Akihiko Iyoda

1. Searching for a “Sound”

Saito:

I’m Daichi Saito from WSS Playground.

Fellow Traveller is seen by many as a champion of narrative indie games. I also see myself as a narrative-driven indie publisher. I have come to seek your wisdom as a mentor in this tough field. Thank you for your time.

Chris:

I’m Chris Wright from Fellow Traveller. A “mentor” sounds far too grand. Anyone surviving in this brutal industry is my comrade. Please, no need to stand on ceremony. Ask me anything.

Saito:

Let me get straight to the point. What does the word “narrative” mean to Fellow Traveller?

Chris:

“Narrative” is our sound.

When I first thought of launching a publishing studio, what initially came to mind were the UK indie record labels of the ’90s – labels like Rough Trade Records, 4AD, and Scotland’s Chemical Underground – all of which started out as small, scrappy groups comprised of music-loving youths.

Back then, each label had its own distinctive “sound” or “flavor.” If you liked one of the bands signed onto a label, chances were you’d like the other bands. The label itself became like a boutique of carefully curated records.

That’s the kind of publisher I wanted to be. Each developer’s work is different, but I wanted to build a brand where the audience could say, “If it’s from this publisher, I can trust it.”

That said, we weren’t necessarily branding ourselves as a narrative-focused publisher from the beginning.

Saito:

It was only after you changed your original name, Surprise Attack, to Fellow Traveller that you fully embraced the narrative theme, right? What were you aiming for in the Surprise Attack era, and why did you decide to change directions?

Chris:

When I founded Surprise Attack in 2011, the idea was to showcase Australian-made games.

That decision had a lot to do with the context of my own personal circumstances. Before 2011, I had been the Marketing Director at the Australian branch of THQ and had just moved into Blue Tongue, one of THQ’s internal studios. It was an invaluable chance to work on the ground with the developers as a marketer.

But then the 2008 global financial crisis upended everything. Australia was full of branch studios owned by overseas majors, and most people in the local industry worked under them. As the recession hit overseas, these branches started closing between 2010 and 2011. Blue Tongue was shuttered, THQ Australia was dismantled, and I lost my job. Soon after, THQ’s U.S. parent company collapsed too.

Many of my colleagues suffered similar fates. There was nowhere to apply now that several major game publishers were gone. Some had no choice but to go independent.

There I was, sharing in the same bitter experience, and all I wanted to do was support Australian indies. That’s when I first thought of starting Surprise Attack and making Australian games its identity.

(The logo of Fellow Traveller’s previous iteration, Surprise Attack.)

But there was a fault in that logic: nobody actually cares where games come from.

Thinking about it now, it’s quite obvious. The only thing that matters is if the game is fun. Being Australian‑made isn’t a commercial advantage by itself. Australian players will support standout local games, but the domestic market is small, so local excitement has limited impact.

The initial business under the Surprise Attack name was rough. For the first two or three years, publishing brought virtually no revenue. We survived thanks to income from our marketing consultancy work. As a founder, I didn’t take a salary.

Chris:

We caught a break in 2015 when Team Fractal Alligator’s Hacknet became a smash hit. That gave us some breathing room. By then, I knew that we couldn’t survive as a company that specializes only in games made in Australia.

We needed a new identity. We had to know our true sound. After many long meetings, we realized the core of our interests was narrative.

(Hacknet was a hit from the Surprise Attack era, before the studio rebranded itself as Fellow Traveller)

Chris:

Narrative games are a goldmine for indie studios with tiny budgets.

High-end 3D visuals usually demand a lot of technology and resources. Likewise, creating fresh gameplay systems from scratch can be costly when it comes to design and programming. Innovation is expensive except in one place: story.

You will never run out of stories to incorporate into video games. Given that fact and our love for narrative-driven titles, we rebranded as Fellow Traveller in 2018.

Saito:

Since the rebrand, recognition of Fellow Traveller as a narrative publisher has spread rapidly among Japanese fans and industry people. By 2020, you had released a string of titles – Neo Cab, In Other Waters, Paradise Killer, and Suzerain – all of which were received positively.

Each title is distinct, yet there’s an underlying sense of consistency. That must be Fellow Traveller’s “sound” that you mentioned. How has the studio managed to keep that aspect of itself consistent over seven years?

Chris:

It’s thanks to the adventurous spirit of our developers.

Fellow Traveller’s game lineup spans many genres, settings, and art styles. But what they all share is an ambition for storytelling. Indies are where developers push new forms of expression. Supporting those daring studios is our mission. We want to move video games forward as a storytelling medium.

Saito:

Why is Fellow Traveller so committed to innovation?

Chris:

Because innovation is the essence of indie games.

AAA blockbusters aren’t devoid of innovation, but they tend to stay within familiar genres and mechanics. With so much money on the line, they can’t take real risks.

In contrast, indie games constantly bring fresh ideas. That cycle of renewal is in gaming’s very nature. When I first started playing games in the 1980s, it felt like every week brought something groundbreaking, be it a new mechanic or game genre. However, that progress had slowed down by the early 2000s. Big studios started pouring more money into established IPs and shying away from risky innovations. I started to feel that the innovative days of the 80s were gone.

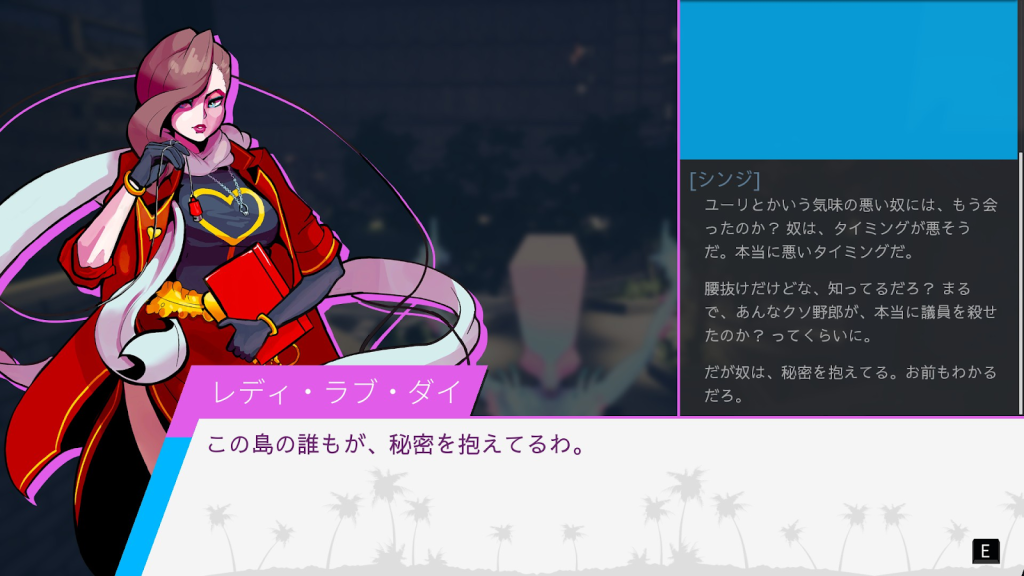

(Paradise Killer by Kaizen Game Works is a mystery adventure game which features unique characters and a world inspired by Vaporwave and Y2K aesthetics)

Chris:

Then came the indie boom of the late 2000s, where small games brimming with fresh ideas made me feel like the golden days had returned. That electrifying sense of discovering something unseen is what I want Fellow Traveller to bring back as a publishing studio.

2. How to Make a Narrative Game – Designing for “Discovery,” “Empathy,” and “Immersion”

Saito:

How do you decide which titles or developers to work with?

Chris:

During the concept stage, our discussions generally boil down to two things:

1. What sensations or emotions will this game evoke?

2. How can those sensations or emotions be conveyed to the player?

Fellow Traveller has a list of factors that we go through together with the developers. The list includes things such as mastery of player skills, excitement, social connection, and competition. While we don’t particularly emphasize these factors, they help frame the conversation better. What matters is finding which of these factors overlaps with the preferences of our target audience.

Saito:

Which elements do you value the most at Fellow Traveller?

Chris:

Three things: Discovery, Empathy, and Immersion.

“Discovery” is everywhere in games. It can be found in puzzles or, in the case of an open-world RPG like Breath of the Wild, environmental observation and interaction. In narrative games, discovery is about finding the next piece of the story. That discovery generates surprise, which is a reward in and of itself.

(The noble stray cat in Citizen Sleeper.)

Chris:

Rewards can be extrinsic (from the game) or intrinsic (from the player).

Extrinsic rewards are when the game praises you or gives you items for completing a task. Intrinsic rewards are when you feel good about your own decisions, even if the game gives you nothing in return.

For example, in Citizen Sleeper, you can feed a stray cat. It doesn’t raise any stats or help you progress. But almost every player does it, because simply giving food and bonding with the cat feels good.

Chris:

“Empathy” is about perceiving in-game characters as real and imagining yourself in their situations.

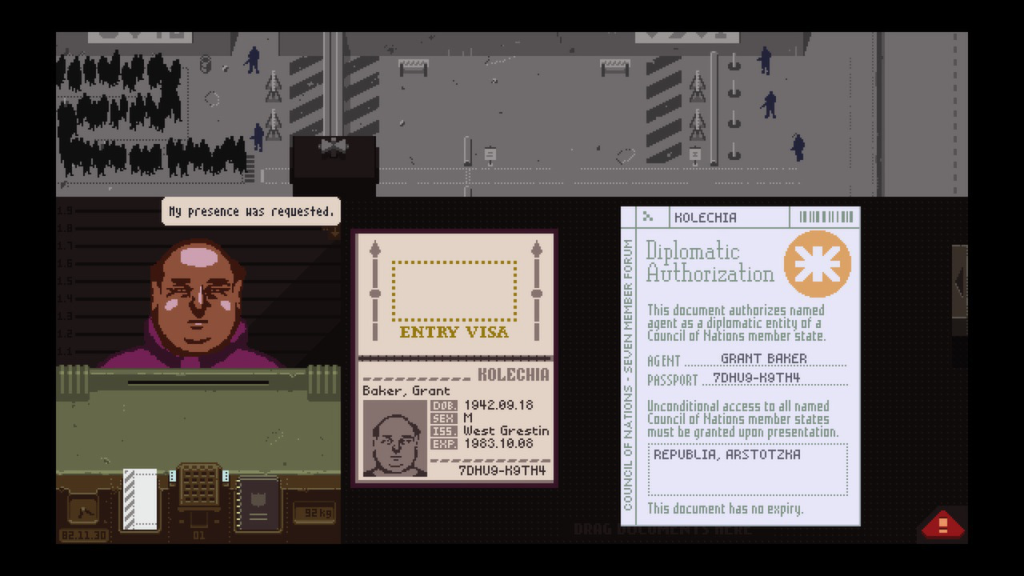

The most effective narrative games put you in someone else’s shoes and get you to feel their dilemmas. Think of Papers, Please, where you are caught between polar political pressures as an immigration inspector. To feed your family, you must follow the rules, but those rules are often cruel and inhumane. The empathy it stirs comes solely from playing the game.

Movies can evoke feelings, but they can’t put you inside the role of the character and allow you to make decisions the same way games can.

(Papers, Please)

Chris:

The third point, “Immersion,” is about creating a world that you can fully immerse yourself in emotionally. Many classic games achieve this. The Legend of Zelda games are a masterclass in this regard.

To fully immerse a player, you need to weave together a strong setting, world, story, and events, all of which create a space worth investing time and emotion in. In a traditional sense, this would normally demand high-quality graphics and game systems, which are generally expensive.

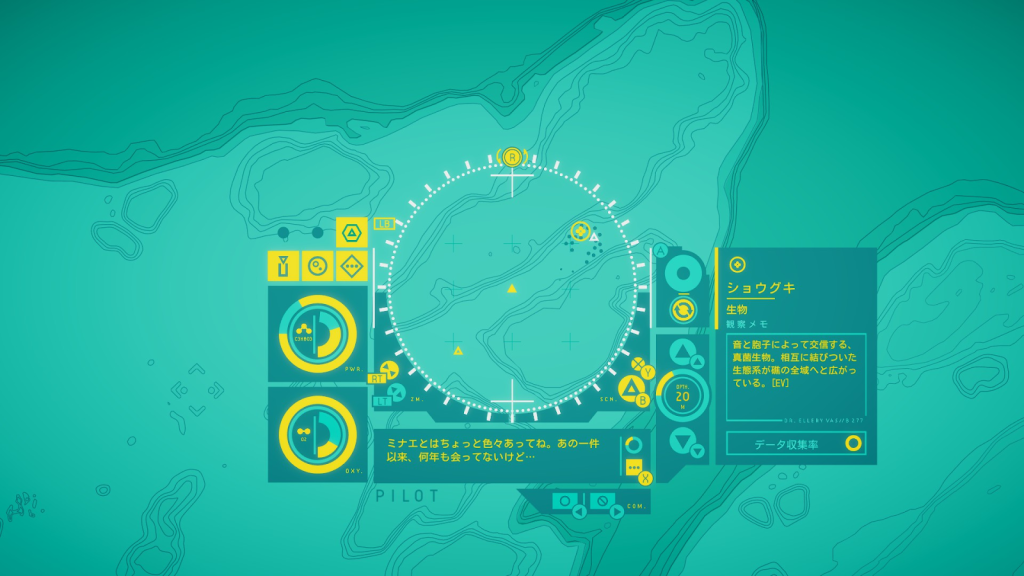

Indie game developers often use their imaginations to thrive under constraints. In Other Waters, for example, barely has any visuals at all. But through text and clever UI elements, the game allows players to conjure a whole alien world in their minds. Sometimes imagination allows us to paint worlds that are just as vivid as any form of CGI.

(In Other Waters, by Jump Over the Age, is a game told from an AI’s perspective. Instead of high-end graphics, the story is told using basic images and a simple yet inventive UI.)

3. Companions on the Journey – Publisher & Developer Relationships

Saito:

As a publisher, how exactly do you build relationships with developers? The name “Fellow Traveller” seems to express an attitude towards collaboration.

Chris:

Exactly. Game development is a journey. We are partners on that journey, but ultimately, it is the developer’s own path. We place them first and focus on supporting their journey.

The term “fellow traveller” also has a historical meaning. In the Russian Revolution, it referred to sympathizers – people who resonated with the cause but did not act directly. As publishers, we deeply empathize with developers’ artistic visions, but we are not creators ourselves. The name reminds us of our position: to support creators and not override their decisions.

(Fellow Traveller logo)

Saito:

What is the first thing developers seek from you?

Chris:

Funding, above all else, followed by marketing. But I believe the greatest value a publisher provides isn’t money. It’s a partnership.

Most of the development teams we work with are tiny and consist of only one to three people. They spend years working in isolation, only surfacing when they release a new title every three years or so. For them, regular interaction with a publisher can be invaluable.

That’s why we hold meetings every two weeks. Sure, we talk about production and marketing, but it’s also about staying connected. Sharing responsibility, carrying part of their mental burden – many developers don’t realize how important that is. Having someone there for you is a huge source of motivation.

Saito:

I’ve always thought the greatest thing a publisher can give is friendship. But as publishers, we also bear the responsibility when it comes to making quality games. That inevitably leads to people voicing opinions about what makes a good game. How do you handle these differences of opinion at Fellow Traveller?

Chris:

First and foremost, final creative authority always rests with the developer. That’s a core philosophy that is written into our contracts. So even if we think something is a bad call, the developer has the right to push it through. All we can do is persuade them.

Saito:

I get that in theory. But sometimes a developer wants to do something that you know will lose the audience. Surely you’ve experienced moments like these before.

Chris:

Honestly, no. Not in that way.

Saito:

Really? Not once?

Chris:

If we need to suggest changes, we usually use third-party perspectives like mock reviews from consultants or journalists. For example, “This story beat is a little unclear,” or “Players don’t understand what’s happening here.” Developers are rarely resistant. In fact, most want that kind of feedback. They want to know how their story is perceived by someone else.

Our greatest concern is making sure we don’t obstruct their creativity unnecessarily.

Saito:

How about progress management? Writers can sometimes be notorious for never meeting deadlines. I’ve even had one experience where a writer left me hanging for a whole year, only for them to not submit anything in the end.

Chris:

We don’t really manage things in a tightly planned way. We assume that developers will finish by the deadline if you give them enough time. Of course, they rarely do. Release dates in game development are like dreams: fragile and fleeting.

The one exception might be Citizen Sleeper’s studio, Jump Over the Age. I’d say they’re the only devs on Earth who actually meet deadlines.

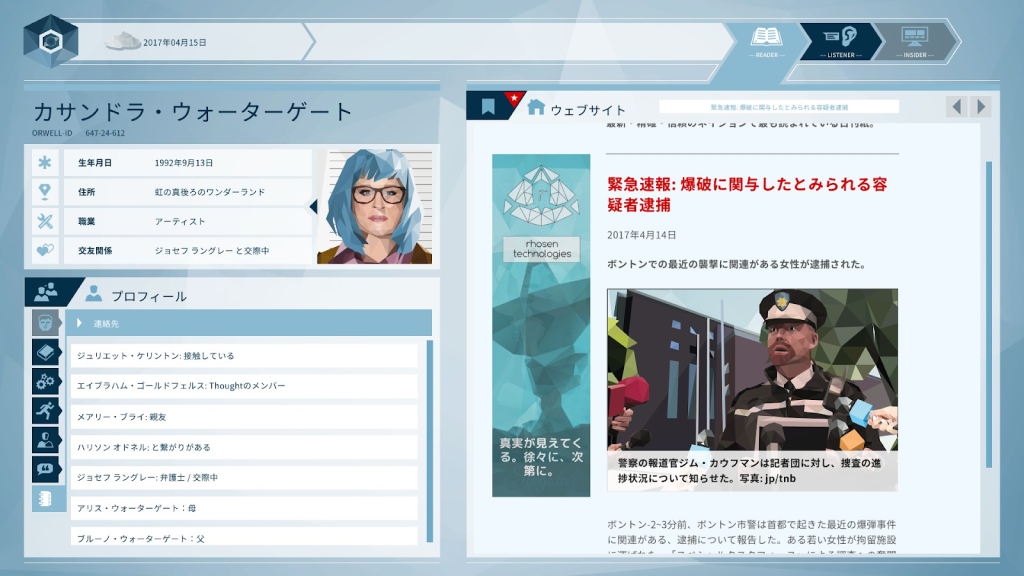

(Orwell: Keeping an Eye On You, by Osmotic Studios, was initially released in an episodic format.)

Chris:

Osmotic Studios, makers of Orwell: Keeping an Eye On You, also has that German sense of punctuality. That game was released episodically, with five episodes being released over the course of one episode per week.

The developers would meet their deadline every week, save for the finale. Just four hours before release, they found a critical bug that forced them to delay the game by six hours. So it wasn’t too bad.

Game development is a complex, unpredictable process. I often tell our publishing team that we are working on water. Everything is fluid and unstable.

Saito:

I’ll admit that I sometimes fight with developers over quality or deadlines. Deep down, I can’t shake the feeling that I should have the final say since I’m the one paying for everything. I never say it aloud, but the feeling is there.

Chris:

Compared to many indie publishers, I think Fellow Traveller is fortunate to have some financial breathing room. That’s because our business has two pillars: indie game publishing and an agency that does consulting for companies with regard to Australian marketing.

That agency business provides steady income. If there’s a shortfall in publishing, we can patch it with consulting revenue. Agency work is simple: you work today, you get paid tomorrow. Publishing is different: you work today, and maybe two or three years later, you get revenue if you’re lucky. It can also amount to nothing at all.

By balancing these two models, we can stabilize both the company’s finances and our own mental health.

Chris:

Developers are the source of both our greatest joys and our greatest sadnesses.

We’ve seen magic happen when a project comes to fruition. Witnessing that miracle is incredibly rewarding.

The worst tragedy is when a game fails. While it’s sad to see our investment fail, it’s worse to see developers, who have poured years of their life into a passion project, be ignored by the world. Watching them get crushed and struggle to get back up is painful. Yet as publishers, it’s our duty to face that reality. It’s the price of admission to this industry.

Like heartbreak, the only cure is time. When failure hits, the first thing we do is care for the developer. It’s hard for both sides, but we say, “Don’t dwell on it. It’ll be okay.” And then we keep walking together.

(Afterlove EP, by Pikselnesia, is a narrative game that deals with the sudden death of a lover.)

Chris:

Tragedy isn’t only about commercial failure.

Take Afterlove EP, which was released in February 2025. The project was led by Mohammad Fahmi, creator of Coffee Talk. But he suddenly passed away during development. The team chose to continue, and we supported them. Without Fahmi’s vision, the road was incredibly hard. But together, step by step, we pushed on to realize what he had imagined.

4. Building a New Platform Through LudoNarraCon

Saito:

Since 2019, Fellow Traveller has been hosting Steam’s annual LudoNarraCon – an online convention that gathers narrative-driven indie titles and creators.

I myself helped launch Indie Live Expo, an online event, so I feel a strong kinship with what you are doing.

Chris:

LudoNarraCon is something we’re proud of. It proves that even a small publisher can launch and sustain a meaningful event.

The inspiration came from my own experience. After we rebranded as Fellow Traveller, we exhibited at many game events. I learned firsthand just how hard it is to showcase a narrative game on a noisy convention floor.

Imagine being handed a controller in a deafening hall and being told to immerse yourself in a story world for ten minutes. It’s nearly impossible. Games, especially narrative-driven ones, need time to breathe. I watched demo players walk away with puzzled looks, and it was frustrating.

Yet developers expect event presence, and it’s undeniable that game shows are the prime PR venues for indies. As we kept exhibiting on show floors, we began searching for an alternative.

(LudoNarraCon is held every spring with full support from Steam)

Chris:

The turning point came at Melbourne Games Week 2018. A Valve staffer was giving a talk on their new Steam video streaming tech, and the crowd reaction was rather lukewarm.

It was a curiosity to many, but I saw potential. What if we could stream demos and talks on Steam itself? What if we could bring the entire convention onto the platform?

We quickly worked out a plan with our marketing lead, pitched it to Valve, and they loved it. They provided the tools, tech, and even promotional support. The hardest part of year one was convincing devs to release online demos. It may have been chaotic, but the first LudoNarraCon was a success. Feedback was so positive that we knew we had to do it every year.

Timing also helped with LudoNarraCon’s success. COVID lockdowns hit by the event’s second year in 2020. Suddenly, online festivals weren’t niche anymore; they were the only option. The mindset shift was dramatic.

(LudoNarraCon developer panel sessions. All past panels are archived on YouTube)

Saito:

Though Fellow Traveller organizes it, LudoNarraCon features a diverse lineup of devs, publishers, and journalists beyond your own network.

Chris:

We’re small. We can’t “save the whole world.” But we can find the games and creators within our reach, and support them.

That’s why we run LudoNarraCon: to give a platform to devs with whom we do and don’t directly publish titles with. By doing so, we expand the field for new storytelling in games. Ideally, we’d like to create similar events that occur at least once a year beyond LudoNarraCon.

5. The Indie Market Now and Ahead – Survival Strategies and Hopes

Saito:

In the past year or two, online algorithms have shifted dramatically. Social media spreads less effectively, and indies that rely on virality are forced to rethink their marketing strategies.

In a 2019 interview, you said that a studio with a fanbase of 30,000 people can be sustainable, provided half of the total fans bought each of the studio’s games.Following the changes in the online landscape, does this rule still hold?

Chris:

For us, yes.

The key is budgeting wisely. Our investments top out at around $250,000 per project. That’s where almost all our games fall now. It’s more than in our early years, but we won’t go higher. The bigger the bet, the higher the risk.

To help mitigate the risks, we launched a co-investment fund called the Treasure Hunters Fan Club to pool investments into Fellow Traveller titles.

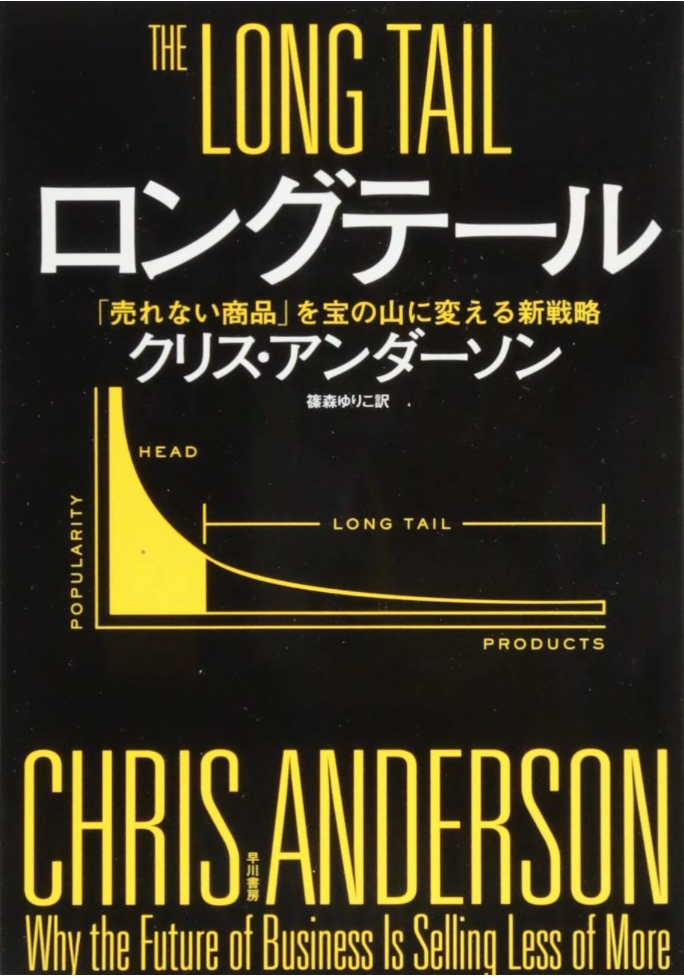

My bible is Chris Anderson’s The Long Tail. I read it 20 years ago, and it shaped my vision of surviving in indie publishing.

Chris:

Anderson’s idea is simple: diversify into niche content and earn steady revenue long-term. Compared to the “short head” of blockbuster-driven markets, the long tail felt far more viable. That’s been Fellow Traveller’s core strategy, and I still believe Steam is the best platform to realize it.

But Steam is no paradise. I see three problems with the platform:

1. Noise. In 2015, when we launched Hacknet, Steam had about 1,500 new releases a year. Now it’s 10,000. Has the number of “good” games increased proportionally? I doubt it. More releases mean the signal-to-noise ratio worsens. Bad money drives out good.

2. Old hits dominate. Some classics keep selling endlessly. Hacknet, ten years later, is still in our annual top five. That helps us financially, but for the industry, it means that new games struggle for attention.

(Hacknet remains in the “Top Selling” section of Fellow Traveller’s Steam curator page)

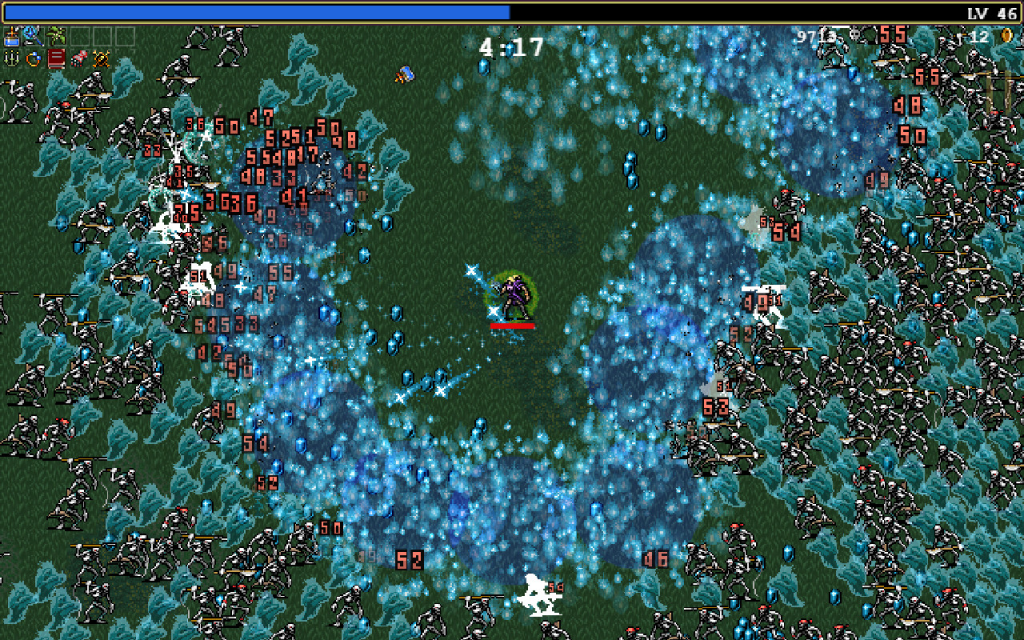

3. The freshness crisis. More games mean faster consumption. Genres burn out. Within six months of Vampire Survivors’ launch, Steam was flooded with similar clones. The same thing happened with local multiplayer titles years back. The pace of consumption makes it hard for truly fresh ideas to thrive.

So the challenge for platforms is to keep the ecosystem fluid. Steam does this better than most, but it is still a big challenge for the people at Valve.

(There are now over 300 Vampire Survivors-Like Games on Steam, according to the Steam tag.)

Saito:

I’m not convinced that the long tail still works. It feels very binary in that games either sell or don’t. Small publishers are at risk, given their limited ad budget and weaker reach on social media.

(Xbox Game Pass, a subscription service offering a wide range of titles from new AAA releases to indie games)

Then there’s subscription services like Game Pass and Apple Arcade. They can be lifesavers in such a way they provide stable income for publishers and developers, thus removing the risk of total failure. But if these services encompass the whole indie ecosystem, won’t that ultimately hurt us too?

Chris:

I share the concern. In a future where every game comes via a subscription, surprise hits like Undertale or Vampire Survivors won’t happen. The medium’s vitality would vanish. What we all secretly want is that moment when an unexpected game suddenly sweeps the world.

Saito:

Language is a hurdle for narrative games. Given that some scripts are so large, localization costs can end up exceeding expectations.

Chris:

It’s a challenge for us too. Our average project has around 100,000 words. Some hit 500,000. So we usually launch games in English first, then add additional languages later. Considering that 55-60% of our sales come from North America, 25-30% from Europe, and 15% from Asia, our primary targets are English-speaking markets.

However, German, French, Spanish, Chinese, Russian, Brazilian Portuguese, and Japanese-speaking markets have potential for major growth, provided we can localize our games for them. Fans of narrative games often play in English even if it’s not their native tongue since they know localization is uncertain. But English barriers in Asia are higher. To reach China or Japan, localization is essential.

(The word count of CITIZEN SLEEPER 2 exceeds 250,000. For reference, a typical novel is about 100,000 words. The Japanese version of CITIZEN SLEEPER 1 was only implemented two years after its official release.)

Chris:

Japan is a special case. As the Nintendo Switch dominates the market, you can’t release a game in the country without Japanese localization. If I had to prioritize one language after English, it would be Japanese.

For Afterlove EP, we included Japanese at launch alongside English and Indonesian, even though the script doubled from 65,000 to 120,000 words and costs hit $20,000. One problem we encountered was that narrative game scripts often change with updates. If you localize too early in development, it locks the game into a specific state. It’s often better to finalize the script first and then localize it afterwards.

Jini:

I get that Fellow Traveller focuses on English first. But if you look at Steam stats, Simplified Chinese now comprises 30-40% of the platform’s total users, overtaking English. Can you afford to ignore that?

Chris:

China is important, yes, but localization is always an issue, and politically sensitive themes in our games, such as LGBTQ and politics, don’t sell well there. For us, Chinese players make up only 2-3% of our total sales. We’d love to reach our Chinese-speaking audiences, but the payoff isn’t the same as, say, localizing in Japanese.

As China, India, and Indonesia’s middle class expands, local developers there will start making hit games of their own. That thought excites me.

(1000xResist by sunset visitor [斜陽過客] was developed in Canada, but its story deals with political issues in China)

Jini:

North America and Europe seem oversaturated. Don’t you need to push into new regions?

Chris:

Perhaps, but we’re a small indie publisher. For us, a game that sells 100,000 units is already a massive hit. NA/EU is still enough by our standards. Times change, but small indie companies don’t have to chase growth. Our survival strategy is to make small, sell small. That won’t suit every genre or publisher, but it works for us.

Saito:

Are there new publishers you see carving out their own “sound”?

Chris:

Hooded Horse, the city-builder/strategy specialist. Their CEO, Tim, is a friend. Strategy publishing looked like a bad bet in 2020 due to the genre’s tiny fanbase and Paradox Interactive dominating the market. Another smaller company, Modern Wolf, even burned itself trying.

But Hooded Horse knows their niche. They raised funds smartly and slipped into the gaps that Paradox left. I admire that instinct.

Saito:

So the indie publisher landscape has a kind of “warring states” feel to it, with each publisher scrapping to survive?

Chris:

Perhaps in Japan. But here, publishers tend to cooperate by pooling funds and sharing risks.

Saito:

Exactly why I wanted to be here with you today. I want to build those circles of cooperation among publishers in Japan and extend them worldwide.

Chris:

Friendship is like stars shining in the night sky. Friends are the wonderful people you get to dance with beneath them. Yes, the industry is reeling from mass layoffs. But there are still new games, publishers, and marketers coming up on the horizon. We’ll dance again.

Saito:

What’s next for Fellow Traveller?

Chris:

We have 11 titles lined up through 2026. Beyond that, who knows? New games always come from unexpected places. In recent years, we’ve been making a point to sign projects from countries we’ve never worked with before. Those projects will be integral for our future as a publisher.

Fellow Traveller is one of indie gaming’s treasures. They’ve released highly artistic, innovative titles for years and managed to survive in the industry’s current era of studio mass extinctions.

Chris Wright’s roots lie in both the ’80s dawn of video games and the ’90s UK indie music scene. His passion for what’s “new” makes him a true indie kid.

And yet, he is also a mature businessman. When asked what he would do if he found a brilliant but utterly unmarketable artistic game, he immediately answered that he would walk away from the project.

Entertainment is a business. Dreams alone don’t pay the bills. That’s why Fellow Traveller relies on both its publishing and agency consulting pillars to survive while carefully choosing who to partner with.

But Wright is not cynical. Through co-investment funds and LudoNarraCon, he tries to expand the frontier for narrative games. Who will Fellow Traveller journey with next, and what story will they tell?