Share

https://int-magazine.com/interview/ludimus-inc-sho-sato/

クリップボードにコピーしました

Interview #9 2025.10.20

It has been over 70 years since the birth of video games. People often say that games are now a universal form of entertainment, a language that transcends both generations and regions.

But is that really true? Has the light of games truly reached every corner of the world?

For example—are there people who play games in Antarctica?

What about inside prisons?

In India? In Central Asia? In the Middle East? In conflict zones? In deserts? In the poorest slums?

Do games exist in those places?

To these questions, there is a man who confidently answers:

“Yes, they do.”

Really? Has he actually seen it, to the very ends of the five continents and the seven seas?

When pressed further, he nods with a smile and replies:

“More or less, yes.”

This man is Sho Sato, CEO of Ludimus Inc., a company that researches game markets worldwide. As an international game market analyst, he travels across the globe, giving numerous lectures each year at government institutions and conferences. Known throughout Japan’s industry circles, he doesn’t just collect reports and data—he sometimes ventures into dangerous places like slums and black markets.This time, the I.N.T., which has been reporting globally on indie game culture, conducted an interview with Mr. Sato under the theme:

“The Present and Future of Asia’s Game Markets and Development Scenes.”

For Japanese people, Asian countries are both our closest neighbors and, paradoxically, some of the cultures that feel most distant.

Take Korea and China, for instance. In recent years, they have become closer to Japan in terms of game culture, but how much do we really know about their backgrounds, their markets, and their visions for the future? And what about gamers in the Middle East—starting with Saudi Arabia, which in recent years has made its presence felt as an esports sponsor?

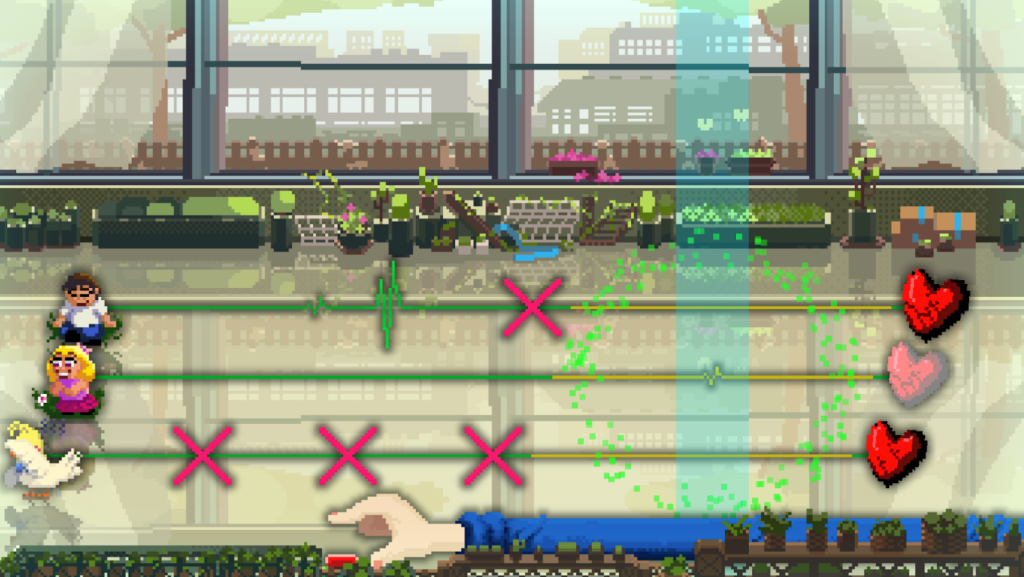

In India, PUBG spread like Space Invaders once did. In Indonesia, a game about a street vendor selling local food called Bakso became a hit. In Kazakhstan, indie game culture is rapidly growing. And in Saudi Arabia, women are taking the lead in nurturing gaming culture.

Why have such developments come about?

Mr. Sato is the ultimate guide to help us understand the background behind them.

This is a grand tour with Mr. Sato as our mentor, taking us from Japan all the way across Asia to the Middle East. By the end of this journey, you too will surely be able to speak confidently about the state of gaming in Asia.

And the lessons extend beyond games—toward a broader international understanding of culture and politics. In recent years, many nations have begun to recognize games as a vital part of their industries. To understand games, therefore, is also to understand economics and politics.

In this interview, which ran for over four hours and produced nearly 40,000 words of transcript—enough to take about an hour and a half to read—we explore every aspect of Asia’s gaming world, from business to culture, from the front stage to behind the scenes. Whether you’re a game fan or a business professional, it is well worth your time.

<The following interview is based on a recording from May 10, 2024.>

Editor & Interviewer / Jini

Interviewer / Daichi Saito

Author / Shu Chiba

Photographer / Akihiko Iyoda

Jini:

I’m Jini, Co-Editor-in-Chief of I.N.T. and chief writer of the indie game media “Game Zemi.” As part of I.N.T., we’ve invited Mr. Sato—who knows game markets worldwide—to dig deep into Asia in particular.

Daichi Saito:

I’m Daichi Saito, also Co-Editor-in-Chief of I.N.T. and head of WSS Playground. Many readers at Dengeki Famitsu Online Gamer already know you, Mr. Sato, but could you briefly introduce yourself?

Sho Sato:

I’m Sho Sato, CEO of Ludimus Inc.

We’re a consulting firm that helps Japan’s entertainment—games, anime, and manga—expand overseas, with a focus on analyzing game markets across countries.

Our strongest area is emerging markets—regions outside the West such as Southeast Asia, South Asia, Africa, and Latin America that are poised for growth.

That said, our network has been expanding in Europe and North America as well. Ultimately, we aim to cover the entire globe.

(Logo of the international content-industry consulting company “Ludimus”.)

Jini:

Why focus your research on overseas game markets—especially the niche of emerging countries?

Sato:

I turned to emerging markets out of a pragmatic need to make a living in my dream field—games.

North America, Europe, and China were already red oceans, and I expected competition to intensify. So I focused on countries that would become key export destinations: emerging markets.

That said, even if Africa is set to grow, it’s tough to expect a massive, investable game market within 10–20 years.

A market promising both economically and in terms of proximity—geographical and psychological—to Japan pointed me toward the Middle East.

While still a student, I looked for a way in. A Jordanian classmate happened to say, “There’s a good job in Jordan.” Perfect timing. I flew there right away.

(Wadi Rum Protected Area, a World Heritage site in Jordan, also a filming location for “Lawrence of Arabia”.)

Jini:

That sounds like everything went according to plan.

Sato:

Except when I arrived in Jordan, the job didn’t exist. My classmate had bluffed.

Jini:

What!?

Sato:

There’s not much you can do after you’ve already arrived.

So I asked Jordanians I’d met to list local game developers, and I went door-to-door asking, “Please hire me.”

It paid off: I got a position at the Jordan Gaming Task Force, an industry group aiming to elevate Jordan’s international profile in games and game development.

Saito:

Haha—what a wild start. I’ve known you for a long time, Mr. Sato, but that’s the first I’ve heard of your job-hunt misadventure.

Jini:

The stumble was epic, but so was the recovery. These days you also cover major markets like North America and Europe. Is there anywhere you haven’t researched?

(First time for I.N.T., but Dengeki Famitsu Online Gamer has interviewed Mr. Sato several times already.)

Sato:

No, there are far more countries I haven’t been to. I’m unfamiliar with the Pacific Islands, for example. And Antarctica…

Jini:

Surely there’s no game market in Antarctica… Right? …There is?

Sato:

Oh, absolutely relevant. There is a game market in Antarctica.

Saito:

In Antarctica!? A game market!? Really!?

Sato:

Of course. Wherever there are people, there is always a game market.

Jini:

I see—people doing research in Antarctica sometimes have downtime depending on the weather…

Sato:

Historically speaking, video games—like “Tennis for Two,” created at Brookhaven National Laboratory—were started by university students and researchers, right? And the majority of Antarctica’s population consists of researchers. They’re real game-loving geeks. When it comes to killing time, games are the first thing they choose.

From what I hear, they play matches over a local area network.

Jini:

Ah, so playing from Antarctica against players in the United States or Japan would be impossible—because of the so-called “lag.”

Sato:

Unless a satellite is directly overhead, communication is tough—so online fighting games or FPS play is basically out. Interviews with local gamers suggest they play via LAN—or offline—within Antarctica.

Jini:

So the LAN culture that’s fading in our country survives in the Antarctic wilds…

Sato:

And speaking of extreme environments—prisons have a game market too.

Jini:

You can play games in prison?

Sato:

Not only can you play—there are platforms dedicated to prisons. A U.S. company called Pebblekick is well-known; they claim top share for prison game platforms and distribute many titles from China and Korea. If they’re “top share,” there must be others, too. FPS titles are off-limits, but F2P, microtransaction-based games are playable.

Jini:

So they spend money earned from prison work? Like the underground empire arc of Kaiji. Prisoners have their own game market.

Sato:

Exactly. I’d like to go around interviewing gamers in the polar regions. In isolated, closed environments, there are always games. And in other places—like military forward bases or submarines. Interested?

Saito:

Absolutely! I’d definitely want to read that.

Jini:

The polar talk is fascinating, but today’s main theme is a “map” of Asia’s game markets.

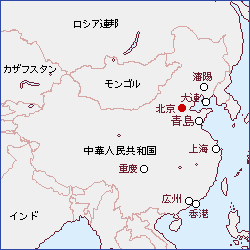

Starting from Japan, we’ll look at neighboring giants like Korea and China, then circle through Southeast Asia, move across South Asia including India, touch on Russia, and finally the Middle East—now among the hottest markets. What are the trends, who are the developers, and how should Japanese companies engage? We’d like Mr. Sato to be our tour guide.

(A global world map used during the interview.)

Jini:

Well then, let’s begin.

First, East Asia—China and Korea. As I.N.T., we reported on Blue Archive, SANABI, and Limbus Company in Korea. And in China, titles like Genshin Impact and Black Myth: Wukong have also become hot topics in Japan.

It may be hard to call them “emerging” either in terms of games or economics, but they are indispensable when mapping the gaming landscape of Asia as a whole.

From your perspective, Sato-san, how do these two countries look?

Sato:

Both China and Korea are among Asia’s most attractive markets. For Japan, cultural and physical access are major advantages.

Given how often titles succeed across Japan, China, and Korea, player tastes are fairly similar—thanks to long mutual cultural influence, from the Four Great Classical Novels* to anime.

Beyond Japan–China and Japan–Korea ties, Korea–China ties are deep too. Historically, Korean PC games were distributed for China, and Korea’s impact on Chinese game culture is underrated.

So the three countries each hold cultural export advantages for one another. Many see China and Korea as mature markets from Japan’s perspective, but I believe there’s still plenty of room to grow.

Especially in China: urban–rural disparities remain stark; lower-tier cities and rural areas still lack full access to content.

Depending on economic conditions, there’s significant room for Japanese games to enter.

*Four Great Classical Novels: Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Water Margin, Journey to the West, Golden Lotus.

(Map from Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) website.)

Jini:

Let’s start with China. Recent Chinese games have scored internationally; it feels like a full-fledged export industry now.

(Genshin Impact.)

Sato:

For Chinese developers, it’s often easier to sell abroad than at home—the domestic publishing license requires effort and connections. Some release overseas first, then “re-import” to China once they scale.

In mobile, you even see global titles that don’t sell in China itself.

In my view, beyond regulation, domestic platforms used to be too dominant. I’ve heard splits were basically 50-50 between platform and developer/publisher—sometimes platforms even took 70%.

There was also a bizarre model where as sales rose, the developer’s share fell and the platform’s share increased.

Jini:

What? That’s the opposite of Steam and other platforms, where higher sales lead to better revenue shares for creators.

Sato:

So paradoxically, “selling too well” was a problem. Developers used to say: “Don’t make AAA—make B-grade.” It was more profitable to control sales.

People were consciously making “nothing too fancy,” which likely made outsiders underestimate Chinese technical prowess.

Jini:

So they already had the latent ability to make original AAA—Genshin and other hits weren’t sudden mutations.

Sato:

Yes. People assume there was some great breakthrough or missing link, but the capability was there—thanks to institutions producing strong programmers and artists, and decades of subcontracting for the U.S., Japan, and Europe.

Then Valve shows up and says, “We’ll take 30%; with higher sales, 20%.” That’s motivating.

Jini:

I always wondered why Chinese devs tense up when domestic platforms are mentioned—so that’s the background.Sato:

Seeking opportunities abroad made Chinese studios obsess over localization.

A hallmark of Chinese games is localization quality—often more thorough than in the U.S. or Europe. I don’t mean just major languages like Japanese or English, but “minor” ones like Arabic. In Latin America and the Middle East, I often see players unaware a title is Chinese.

(Genshin Impact.)

Sato:

Generally, European companies are strong at localization; American companies surprisingly less so—because their domestic market alone can sustain them. That size pulls them inward; Latin America, despite its proximity, is often neglected (with some exceptions running via Miami hubs). Europe, with its multilingual reality, pays more attention to language.

China goes a step further—with powerful on-the-ground sales execution.

The ability of Chinese people to market and sell to the world is truly remarkable. In particular, the Chinese diaspora’s networks are formidable. I’ve traveled to many countries around the globe, and there wasn’t a single one without Chinese people.

Jini:

So it’s not just Chinese games—Chinese industry people are everywhere?

Sato:

Everywhere—Middle East, Central Europe, South America, Africa. And they often have good local relationships.

With developers and communities alike. They don’t just sell—they run tailored offline events anywhere.

Jini:

So Chinese content penetrates markets partly because of this communication strength?

Sato:

They run on a different execution engine. European and American firms will often just set up a local legal entity and call it a day—put a Westerner at the top and leave the rest to local staff. The attitude is basically, “as long as you hit the numbers, that’s fine.” They don’t look under the hood—into the underlying substance or the market itself.

By contrast, Chinese HQ staff go in person, observe the realities on the ground, and, through repeated discussions with local people, roll out plans tailored to that locale. Being able to do that properly is, I think, a key reason for their success.

Sato:

About a decade ago, when I began writing game business reports, Chinese games weren’t that dominant in the Middle East or East Asia—European titles like Clash of Clans led.

In five or six years, rankings flipped to Chinese titles. Today, Chinese companies account for over half of emerging-market game sales.

That’s the result of deft “localization”—of both people and products.

Jini:

Tencent’s Leo told me something similar (*). Japan often just “sets up an entity and calls it a day,” too. Why can China push so actively worldwide?

Sato:

A deep bench of international talent. Exceptional Chinese professionals build networks abroad, form good local ties, and become the new overseas Chinese. There’s even a story of a Chinese man becoming a chieftain in Nigeria—the vitality is striking.

By contrast, “Japanese overseas networks” feel less present.

Saito:

In business, you can’t rely on the Wakyō all that much. It’s partly unavoidable given the historical and cultural differences from the Overseas Chinese, etc.

Back in the Shōwa era, reps from Japan’s general trading companies (sōgō shōsha) posted overseas had to sort out trouble on their own, so many were extraordinarily tough. It was very much the mindset that, if you were a sōgō shōsha rep, you were expected to negotiate in person—even with the local mafia—putting yourself on the line if necessary.

Sato:

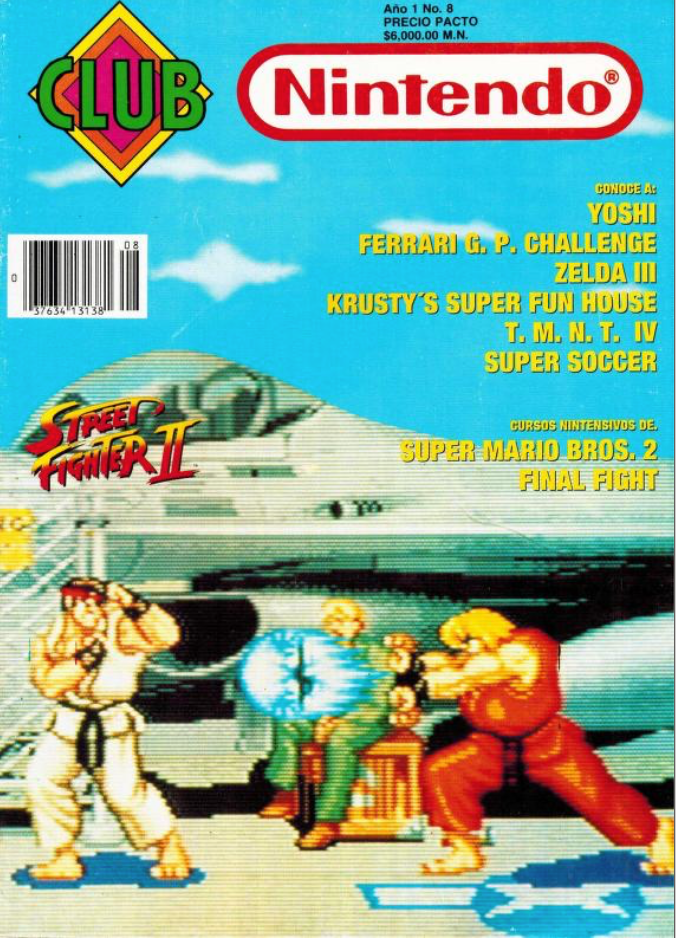

That was trading companies in the old days. Even in games, trading firms were among Nintendo’s early partners in emerging markets.

For example, industry folks in Mexico told me a Japanese trading company launched a high-quality magazine called “Club Nintendo Mexico.” Their long-term vision wasn’t just to entertain current kids, but to cultivate future adults who would, in turn, buy games for their own children. Through that magazine, kids effectively promoted the NES and nurtured a game culture.

Even today, Mexican game people say, “Thanks to how hard those Japanese trading houses worked back then, Nintendo’s brand power remains high here.”

(“Club Nintendo Mexico”)

Saito:

The ’80s really were something.

Sato:

The ’90s were wild too. Take Mr. Ōwada—he marched into China’s black markets, confronted pirate vendors with, “Why sell bootlegs? Buy licensed goods,” and got cigarettes tossed at him for it.

Jini:

No way…

Saito:

Ordinarily, that gets he killed.

Sato:

There were other cases—like ○○ doing ✗✗, turning ■■ into ◇◇◇ and then ▽▽…

Saito:

Hahaha… if we printed that, it’d get you—and us—killed, right?

Sato:

Possibly.

At any rate, it’s true the number of such vanguard types who open up overseas channels has dwindled.

Jini:

They sound like early-modern Christian missionaries.

Sato:

That’s a keen analogy. I often do market surveys in slums; the non-locals you find there are usually missionaries. I once ran into one and we really hit it off swapping slum stories from India and Kenya. In Japan, almost no one can talk shop with me in this domain.

Saito:

So missionaries are like pioneers of BOP (Base-of-the-Pyramid) marketing?

And today, it’s Chinese game operators doing the same thing commercially?

Jini:

I’ve heard Tencent builds games after pre-calculating the marketing from data collected across its hundreds of global offices.

Hearing you, I’m convinced that really is true.

Sato:

Exactly—their marketing schemes are impressive.

Jini:

China is selling games like crazy—but in emerging markets, doesn’t that trigger disdain or backlash against Chinese products?

Sato:

At the citizen level, not really. As I mentioned, their localization is so good many players don’t even realize a title is Chinese.

It’s government—administrative and legislative bodies—that care about “being Chinese.”

You saw how India temporarily blocked PUBG at one point; at the political level, some countries are wary of China-made games.

(CNN article reporting India’s PUBG ban)

If your market share and presence get too big, people start branding it “cultural invasion,” which invites pushback.

With such export power, Chinese games inevitably cause friction in places.

Jini:

Beyond capital and tech, the industry’s people-network tradition amplifies China’s marketing and export presence. On the flip side, political issues in the background can drag things down—is that fair?

Jini:

Next, could we get your impressions of South Korea?

(From Wikimedia Commons)

Sato:

This applies beyond games, but Korea operates with clear national vision and planning. They regularly publish a “Korean Game Industry Strategy” white paper—analyzing the current state and charting direction.

Lately there’s been news—even in Japan—that Korea is finally committing to premium, buy-to-play console/PC titles. Historically strong in F2P online PC and mobile, they’re trying to shift their DNA.

(From the official “Lineage” series site)

Jini:

Why push a nationwide shift toward buy-to-play console/PC?

Sato:

Because they want to expand IP across media. There are IPs that online PC games simply can’t incubate. Lineage sells, yes—but media-mix expansion from Lineage is hard.

With console/PC, that’s far easier. Watching Nintendo and Sega’s IP playbooks, Korean players have caught on. Big firms like Smilegate, Nexon, and Krafton are starting to cultivate buy-to-play titles; Nexon’s sub-label release Dave the Diver is part of that.

Public and private sectors are moving in step toward premium. This year’s hit Stellar Blade likely fits that larger trend too.

(Dave the Diver)

Jini:

Korea evokes net cafés—PC bangs. I assume, like in Japan, the scene has changed a lot over the decades. What’s it like now?

(People playing StarCraft at a PC bang From Wikimedia Commons)

Sato:

From the ’90s boom to now, Asia’s net-café culture—led by Korea—has gone through roughly three generations.

Generation 1: when households didn’t yet have PCs. Net cafés were places to access a computer at all.

In Korea, the PC-bang boom coincided with the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. During deep recession, ordinary people used PC-bang computers to job-hunt. That’s the origin of Korea’s net-café culture.

Jini:

No jobs, no money. No money, no PC. No PC, no job hunt—so they went to PC bangs. And since that’s depressing by itself, “might as well play games,” especially as broadband rolled out.

Sato:

From there you get the sprouts of PC-bang culture—and Korea’s e-sports culture.

Southeast Asia isn’t so different; Brazil’s “lan houses” and Turkey’s coffee-shop-derived PC game cafés blossomed from similar origins.

That’s Generation 1.

Generation 2 is when PCs reached households. Cafés started declining—store counts visibly dropped; clearly a sunset industry. But they didn’t stop: they pivoted to value-add differentiation to survive.

Example: mass-install high-spec/gaming PCs to attract e-sports players and aspirants.

It wasn’t just self-help. NVIDIA has long supported net cafés; in India they even published a net-café operations guide—down to recommended snack pricing. It’s a fun read.

(Net café in South Africa (Wikimedia Commons From Wikimedia Commons)

Jini:

You mean NVIDIA—the global semiconductor company, that NVIDIA, right? Are they the ones creating an operations manual for internet cafés?

Sato:

From their perspective, internet cafés that purchase PCs in bulk are essentially major clients.

Up to that point, that’s the Generation 2

Generation 3 aims to be the hub for local game communities.

In the smartphone era, even demand for PCs dips; you can’t be picky. The industry consolidates into big franchises.

Against this backdrop, these cafés—rather than limiting themselves to PCs or consoles—are enhancing facilities for live game streaming, hosting small-scale esports events, setting up console-gaming corners, and even incorporating mobile, turning themselves into community hubs open to anyone, anytime in order to attract a broader audience.

By the way, there’s even a “world’s first mobile game café” in Bali, Indonesia. Heard of it?

Jini:

In Japan, “game bars” with consoles were later cracked down on, but abroad those spaces still exist. A mobile-game café though? Customers bring their phones and play at the café? That’s …

Sato:

A normal café.

You sit, order snacks and drinks, pull out your phone to play, chat with friends. The evolved net café is indistinguishable from an ordinary café.

Jini:

That’s fascinating. Since the early “coffee-house,” the essence of cafés has been a hub where people gather, talk at length, and exchange ideas. Net cafés, once off that mainline, have looped back to that core.

In Japan, though, net cafés haven’t leaned into community—they tend toward private cubicles.

Sato:

America is similarly individual-oriented. LAN party culture flourished in regional cities, but net cafés became niche—used by newly arrived immigrants for job searches, etc. It’s a survival strategy of its own.

That said, the global decline is undeniable, and operators in each country are seeking their own survival plays.

From a researcher’s perspective, net cafés are the best place to meet a country’s gamers—see behaviors at a glance and talk to community leaders.

Tough for owners, but endlessly interesting to visit as a customer.

Jini:

We’ve got a good sense of China and Korea. Let’s head to Southeast Asia, a growth market for the years ahead.

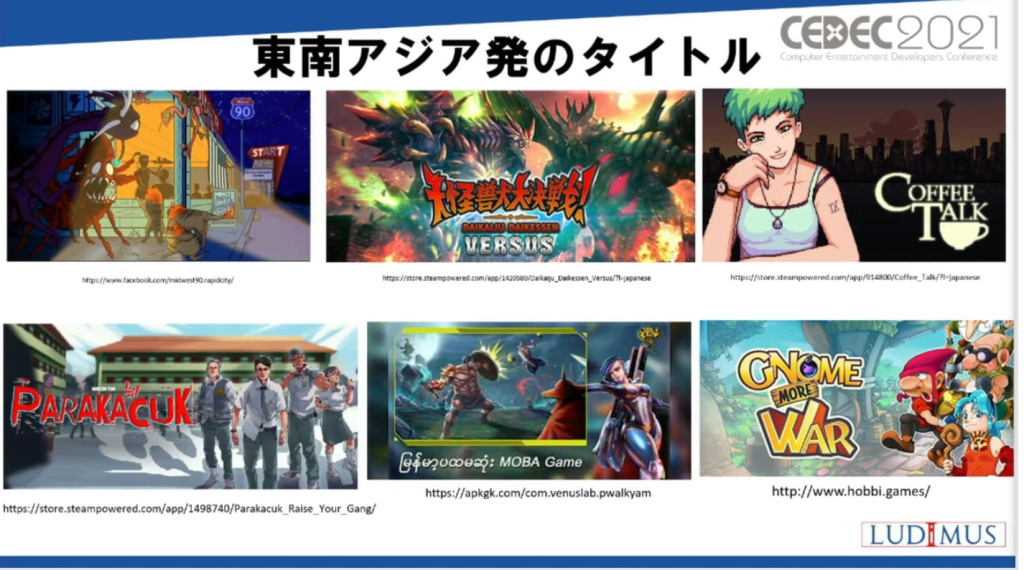

(A collage of Southeast Asia–origin titles introduced at CEDEC 2021.(https://news.denfaminicogamer.jp/kikakuthetower/210830i))

Sato:

To judge a country’s future prospects in games, I look at several conditions:

(1) Macro-economy. That dictates purchasing power. When the economy sours, informal markets expand; legit purchases fall, and even in F2P models, payer ratios drop sharply.

(2) Technical base. Even where original IP seems scarce, long histories of subcontracting for the West or nearby game powers often yield formidable skills.

(3) Population. This matters both for consumers and for talent. The younger the demographic skew, the better—games start as youth culture.

(4) Cultural climate. Religion, institutions, politics, history, temperament, myth, literature, game communities. Even with sound economics/tech, culture can constrain game growth.

Keep these in mind as we analyze the emerging markets ahead.

(From Wikimedia Commons)

Jini:

Let’s start with Indonesia. Indie studios like Toge Productions (Coffee Talk) and Mojiken (A Space for the Unbound) have drawn attention in recent years.

With over 270 million people and a youthful skew, it looks promising as a market.

(A Space for the Unbound—widely nominated for awards.)

Sato:

Coffee Talk and A Space for the Unbound are comparatively export-oriented—aimed at the Anglosphere, with Indonesian culture blended in to create an “Oriental” mood, and well-crafted as games.

But the bellwether for Indonesia’s future will be domestic-facing titles.

For example—Jini, do you know Bakso Simulator?

Jini:

Bak… what’s that?

(A bowl of bakso—meatball soup—via Wikimedia Commons.)

Sato:

Bakso are beef meatballs served in soup—think Japanese tsumire (dumpling-style meat/fish balls)—and they’re a beloved everyday street food in Indonesia. Bakso Simulator is a kind of management sim where you have a local older man (not a relative—an ‘ojisan’) push a bakso cart to earn money. It has roughly 1,500 user reviews on Steam, the vast majority from Indonesians. It’s free-to-play with paid DLC, and the mobile version has over one million downloads.

Saito:

From the review count, we’re talking tens of thousands of players—inside Indonesia alone. That’s impressive.

Sato:

Its momentum has now spread beyond Indonesia, and we’re starting to see Japanese- and English-language reviews because of the novelty. But the title is clearly aimed at Indonesians.

And it lands: it resonates squarely with the target audience, generates buzz, and sells—a self-sustaining cycle on domestic demand alone. It may be hard to grasp from Japan, but achieving true “local production for local consumption” in games is nothing short of extraordinary.

(A German-language Steam review for Bakso Simulator sharing a home recipe.)

Jini:

How did Bakso Simulator spread?

Sato:

It really comes down to word of mouth. WhatsApp and other social media are strong, of course, but offline, face-to-face word of mouth is also very powerful. This isn’t simply about national temperament; it’s partly due to past government policies as well. In Indonesia, people are almost always out with friends.

Japanese folks hang out in front of convenience stores too, but in Indonesia the crowds are on a different scale—far larger—and you’ll see people sitting in circles playing games. That kind of community-driven, local word of mouth really takes hold in Indonesia.

There’s also Troublemaker—a “Yakuza with Indonesian high-schoolers.” It did well; a sequel is confirmed.

(Troublemaker)

Sato:

For local indies, these titles are a huge morale boost. Given Indonesia’s price levels, if you can sell on the order of tens of thousands of copies at typical indie price points, that’s a big success. Even games that only Indonesians would really ‘get’ might actually let their creators make a living. The emergence of that hope is, I think, a major shift in Indonesia over the past three or four years.

Saito:

And if you sell to just 1% of Indonesians (270M), that’s nearly 3 million units—a megahit. Astoundingly attractive market.

Jini:

Indonesia is also a Muslim-majority nation. Are there religious conflicts with Japanese/Western games?

Sato:

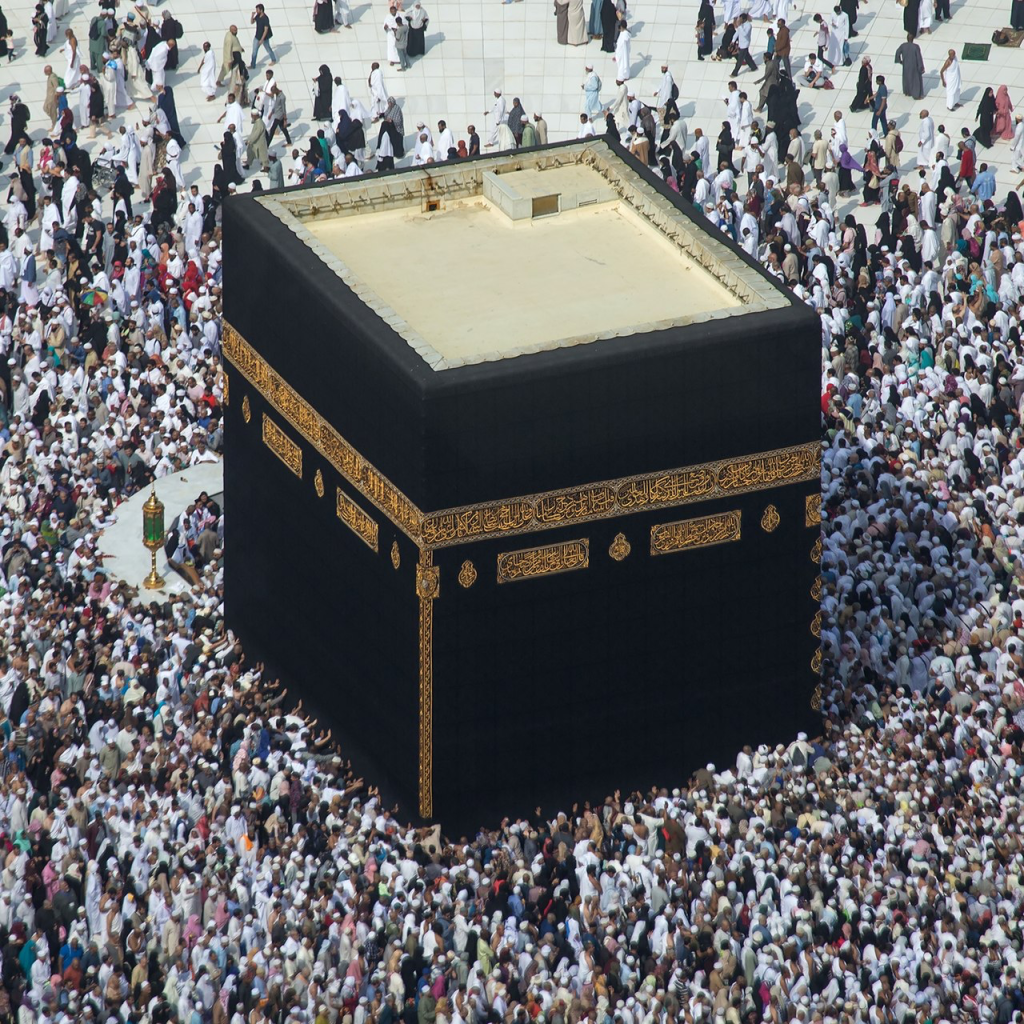

Naturally.

One case that made waves in Japan: Fortnite. A rumor claimed a user-made Kaaba (the Mecca shrine) was destructible, sparking outcry and even a statement from Indonesia’s tourism minister—a political issue.

(https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3140205/fortnite-faces-ban-indonesia-after-minister-brands-it)

(The Kaaba in Mecca. Wikimedia Commons.)

Sato:

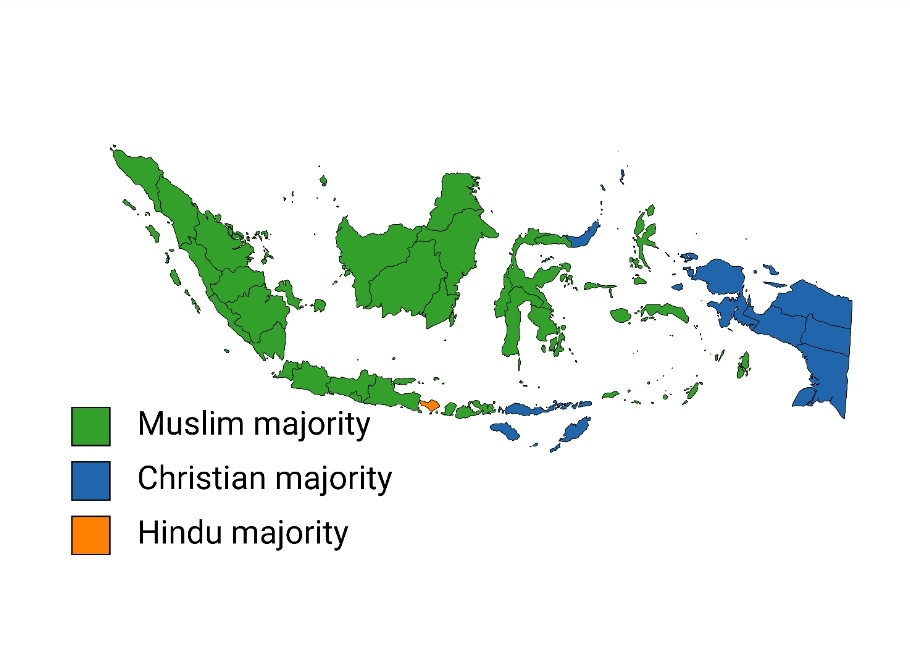

Across Indonesia, faith varies by region/island—strict and less strict Muslim areas, Christian-majority areas—ethnic/ regional differences abound.

Though media report religious tensions, pre-independence Indonesia often managed coexistence.

For example, when wild boars ravaged fields, Muslims (who avoid swine) would ask Christians from a neighboring village to cull them.

But as a modern nation-state forms, ethnic ego and nationalism arise. When “stoking division” becomes a winning electoral tactic, interfaith relations inevitably sour.

(Religious distribution map of Indonesia. Wikimedia Commons.))

Sato:

Indonesian politicians simply can’t afford to ignore the voices of the devout.

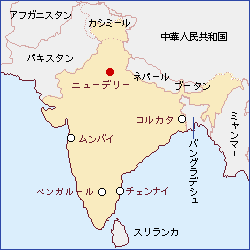

While people often associate Islam with the Middle East, the country with the largest Muslim population is actually Indonesia. Pakistan is second and India is third—all are in South or Southeast Asia.

Muslims in these regions have a unique sense of solidarity. Because the Hajj (the once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimage to Mecca) is so expensive, communities pool and manage funds—similar to Japan’s tanomoshi-ko—to cover the costs. This process strengthens their fellowship through faith.

Jini:

As for taboos—The Act of Killing made the “30 September Movement” and the tragedy of the Indonesian Communist Party widely known in Japan. As the industry matures, we might hope for indies tackling such themes…

Sato:

I don’t know a title tackling the incident head-on, but Let Me Out is set in that era.

The current government doesn’t dismiss games as an industry. Blocking the Epic Store or Steam isn’t only cultural/religious caution; protectionism plays a role. As the domestic entertainment market expands, low local-title share is alarming.

(Coffee Talk—USD 550k in week-one sales)

Sato:

Indonesia now recognizes the need to cultivate games as a national industry. Other Southeast Asian countries will likely adopt protectionist stances too.

Korea has already included online games in its FTA items with Indonesia. Countries are realizing such clauses exist—and can be negotiated.

Jini:

Japan can’t neglect diplomacy here.

Sato:

We don’t want to look up and find Japan left behind. Indonesia is discussing requiring local partners for publishing; Vietnam shows similar moves.

Every nation is eyeing emerging markets; Japan must respond promptly to avoid missing the boat.

Jini:

Since Vietnam came up, let’s talk about that now.

(Vietnam map via Wikimedia Commons.)

Sato:

Geographically and historically, Vietnam is China’s backyard. Despite political frictions, China’s cultural influence is heavy—e.g., Wuxia IP popularity. In games, Vietnamese firms have competed to bring Chinese hits into Vietnam.

Jini:

Speaking of Vietnam, NFT games like Axie Infinity were a hot topic for a while.

(AXIE Infinity)

Sato:

NFT has cooled in Japan/US, but it’s still hot in parts of Southeast Asia and Latin America.

What do those countries share?

Jini:

Low trust in centrally issued currency?

Sato:

Exactly. Bitcoin emerged as an antithesis to centralized state systems—a substitute for central banks. Paid in Argentine pesos or in Bitcoin: which would you choose?

Likewise, NFT thrives where central government is weak. When speaking with companies/communities in such countries, be mindful of that context. You needn’t agree—but at least nod, “I see.”

Saito:

Vietnam long carried a subcontracting image. Is it now positioned to create IP like Indonesia?

Sato:

Not quite yet. Vietnam had the legendary casual hit Flappy Bird, but after that, standout Vietnamese-origin IP has been sparse. There’s strong programming talent, and a publisher association formed recently, but I don’t see prominent industry-wide events. Here, Southeast Asian countries differ.

Going into detail about the game development industry for every single country would make this too long, so let’s just quickly survey the landscape.

(Malaysia map; Rhythm Doctor screenshot.)

Sato:

Alongside Indonesia, Malaysia is vibrant in homegrown development. Think 7th Beat Games (Rhythm Doctor) and Metronomik (No Straight Roads)—it has many lively indie studios.

Jini:

Larian Studios (Baldur’s Gate 3) has a Kuala Lumpur studio as well.

(Rhythm Docter)

(Singapore skyline via Wikimedia Commons.)

Sato:

Singapore is tricky. There’s solid tech from years of subcontracting for global majors, yet few home titles emerge. Small land/population is one factor, but outsourcing culture runs deep. Game-school grads often head to big foreign firms rather than strike out solo.

(Thailand map via Wikimedia Commons.)

Sato:

Thailand’s homegrown momentum is also low. Like Singapore, it has long subcontracted for China/Japan—so there’s a large dev population, but little cohesion, and comparatively weak state support.

A key weakness is the intergenerational gap: veterans shaped by outsourcing vs. new independent creators—too far apart to collaborate. History here backfires. Still, promising indies are emerging (e.g., Lost and Found Co. at LEVEL UP KL 2024).

Market-wise, Thailand is often cited as best balanced—console/PC/mobile—within Southeast Asia.

(From Wikimedia Commons)

Sato:

The Philippines. There are three blocks—Luzon, the Visayas, and Mindanao—but in terms of the game industry, Luzon is essentially the key region.

The developer community climate is healthy. Some independents collaborate with each other, while others skillfully take on subcontract work for the majors via U.S. publishers and make money where they can—overall striking a good balance.

Then, swinging around the coast of the Indochina Peninsula—Myanmar and Bangladesh… well, they still don’t have much bandwidth to be making games yet. That said, in Myanmar I’ve heard the revenue from a certain mobile game has become a funding source for anti-government (opposition) forces, and I’m currently looking into it. In Bangladesh, there are games about the war of independence from Pakistan. Laos and Cambodia each have game studios as well, though the numbers remain small. This is the sort of area where peeking into the informal market gets interesting.

https://www.nna.jp/nnakanpasar/backnumber/210401/topics_001

https://slowinternet.jp/article/informal_market08/

(Articles by Sato on the informal market; other media.)

And with that, we finally arrive at India.

Jini:

You’re keeping track of way too many countries.

(From Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs website)

Sato:

As with other industries, India is a highly promising market. Its population is massive, and growth remains solidly positive.

That said… there are many business challenges. First, video games have a short history there.

Saito:

“Short” meaning games only took off in the 2000s or early 2010s?

Sato:

Not even that. Do you know the first game to become a huge hit in India?

Jini:

PUBG, right? The mobile version.

Sato:

Exactly. It’s now Battlegrounds Mobile India. Since distribution began in 2021, India’s “game history” is, functionally, only about three years old.Saito:

That’s incredibly recent.

(PUBG: Mobile on Google Play.)

Sato:

Of course, small gaming communities did exist in India. For example, Sega once sold home consoles there through an agency, and some of those fans still remain today. But that was only a tiny niche—gaming only became widespread after the smartphone era. It’s also only very recently that India’s previously fragmented regional mobile carriers have consolidated into nationwide networks.

In other words, PUBG is to Indians what Space Invaders was to the Japanese in the 1970s. Just as the average Japanese person back then equated “video games” with Space Invaders, today most Indians equate “games” with PUBG.

So when you talk to them about games, their first reaction is often, “What kind of PUBG (battle-royale game) is this?”

And when it comes to FPS titles, it’s like, “Wait—there’s a PUBG you can play alone!?”

Jini:

Just like how early FPS were all called “Doom clones.”

Saito:

Why did mass adoption come so late?

Sato:

Because other homegrown entertainment is overwhelmingly strong—films and cricket dominate.

Movie tickets can be astonishingly cheap—even in cities, sometimes ¥100–¥300; concessions can cost more. Living standards in rural areas remain low.

Wealthy urbanites can study abroad and enjoy a wide range of entertainment, but such people are only a small minority. The one form of entertainment that even the poor in rural areas can enjoy in common is Indian cinema.

Saito:

In the IT world, it seems like Indian executives are everywhere these days. Don’t those globally active Indian elites ever think about bringing the kinds of entertainment they enjoy back home to India?

Sato:

Some globally successful Indians do return home, yes. Some have even founded venture capital firms and begun investing in mobile games. It’s only a recent development, but thanks to that, we’re starting to see original IPs emerging from India.

Titles like Raji: An Ancient Epic and Asura: Vengeance Edition have drawn attention. Both are action games inspired by Indian mythology and folklore. Games that feel “distinctly of that country” tend to be well received, especially in Western markets.

Sato:

However, within India, developers are still effectively forced to make PUBG-style battle royale games.

At the IGDC, a major Indian game event where I gave a talk recently, the game everyone was talking about was Indus—an Indian-themed battle royale.

Saito:

India has the technology, the talent, and the culture; it’d be great to see more genres than just battle royales.

Sato:

I served as a judge for the India Game Awards last year, and I can sense the beginnings of studios trying to create their own original IPs.

Recently, a game called Mumbai Gullies—essentially a Mumbai-set Grand Theft Auto—was announced. It aims to capture that distinctive flavor of Indian cinema while seriously attempting a GTA-style experience, which looks quite intriguing. Reports also suggest that more players are now exploring genres beyond battle royales, and several studios have begun developing their own original IPs to meet that shift—a very encouraging sign for us.

Jini:

The demand for game streaming seems extraordinarily high in India’s gaming community. On YouTube Live, Indian PUBG streams often snatch the No. 1 spot for concurrent viewers.

Sato:

Game streaming is extremely popular. One major reason PUBG caught on so widely in India is thanks to streamers. In other words, games are creating human connections, communities—indeed, culture itself.

When Indian audiences converge, the view counts explode.

For example, the Singapore tournament for the major battle-royale title Garena Free Fire once surpassed the League of Legends World Championship finals for concurrent viewers. The largest share of that audience was Hindi-speaking.

What’s fascinating is that, due to visa issues, there weren’t any Indian players competing in that Free Fire tournament.

Jini:

So Indians were getting hyped watching foreigners play each other?

Sato:

Exactly. This shows that an esports scene can flourish purely within developing markets. Sheer population size becomes a decisive advantage for a language community.

Jini:

As you said before, each Indian state speaks a different language. There are over twenty major languages, and neighboring states often can’t understand each other. Doesn’t that fragmentation pose a problem here?

(Map of Indian states — from Hiroshima University’s “State Politics in India” site)

Sato:

True, but some states alone approach 100 million people, and when you include emigrants, each linguistic sphere can easily exceed that.

The largest is Hindi—well over 300 million speakers domestically, and 500–600 million including second-language and overseas speakers. That raw demographic scale directly underpins the depth of India’s streaming culture. Of course, India has divisions beyond language, which complicate things.

Jini:

You mean the caste system?

Sato:

Yes. Although discrimination is constitutionally banned, it remains entrenched, and the balance varies by state. For instance, Brahmins—the highest caste—are relatively few in Tamil Nadu in the south, reflecting Hinduism’s historical spread from north to south.

Tamil Nadu, with its thriving film industry, has many non-Brahmin communities like Vaishyas, and numerous Tamil films openly criticize villainous Brahmin characters.

Jini:

They’re allowed to make films like that?

Sato:

Absolutely. In fact, regional party leaders sometimes come from the film industry. The ruling party in Tamil Nadu, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, is led by M. K. Stalin—whose father, M. Karunanidhi, was a screenwriter known for exactly such films. And yes, “Stalin” is indeed named after that Soviet leader.

That said, Brahmin communities differ by region—strong in IT in some places, less so in others. One nationwide pattern: many restaurant owners are Brahmins.

Jini:

I thought Brahmins were mainly priests and scholars.

Sato:

Here’s the logic: Brahmins are highly literate and well-versed in Hindu scriptures, so they know exactly which ingredients are permitted. People thus assume that a Brahmin-run restaurant serves “safe” food.

Saito:

It makes sense once explained, but it’s opaque at first glance.

Sato:

That’s precisely the challenge of marketing in India—the bar is high. Even seasoned businesspeople grumble, “India is inscrutable.”

Surveys from different firms can produce wildly different results. Treat it like other markets and you’ll find it bafflingly complex.

Saito:

Making games for India sounds tough—Southeast Asia seems far clearer.

And even hits risk bans like PUBG or Free Fire. That’s hard for devs; there’s no guarantee Japanese titles won’t be targeted too.

Jini:

When discussing China earlier, you mentioned India’s PUBG ban. From India’s perspective: while it was part of broader restrictions on Chinese apps like TikTok, wasn’t there also a general backlash against games themselves?

For many adults, games are unfamiliar and trigger knee-jerk aversion that spills into moral panic—Japan and the U.S. went through this too.

Sato:

Distrust of games does exist. The medium has only recently gained broad recognition in India, so many haven’t caught up—and plenty conflate “gaming” with gambling.

There’s another thorny factor in India and other emerging markets that further fuels headwinds against games.

Religion.

Most games played in these markets are online, which intersects with sensitive issues.

Beyond Indonesia’s Fortnite flap, there was an incident in India about two years ago: reports surfaced of a Muslim cleric attempting to gather Hindu youths in an online game and convert them to Islam.

Saito:

That’s explosive—especially in a country that literally split with Pakistan over religion.

Sato:

It is. India has the world’s third-largest Muslim population, but proselytizing is often restricted or banned by state law.

As a non-Asian example, Mexico is eye-opening: poor youths playing Free Fire get DMed in pick-up matches—“Got a good job for you.”

The “job” is cartel mule work. In Japan, shady gigs spread via social media; in Mexico, cartels use online games directly for recruitment.

Used that way, games naturally attract public resentment. You can argue “that’s the internet, not games per se,” but it rarely persuades.

In Indonesia and Mexico alike, the social backlash far outstrips what Japan or the U.S. experienced back in the day.

Jini:

Unlike the Space Invaders moral panic, video games are now blamed as part of very real digital-age harms.

Sato:

It’s especially fraught when religion is involved; it touches state structures. If unfettered online expression seems to threaten the current order, authorities push back.

As with any overseas venture: misread religion at your peril.

In short, India’s economy and education are advancing rapidly, but other entertainment looms so large that game culture remains underdeveloped.

(Pakistan map via Wikimedia Commons.)

Jini:

Let’s head further west—to Pakistan, India’s old rival. India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar once formed British India.

Economically Pakistan trails India, but with about 240 million people it has nearly twice Japan’s population.

Sato:

To understand South Asia, you must factor in the Middle East. Historically the ties are deep.

Oil wealth drew waves of South Asian migrant workers—and in games, Pakistani esports players head to Gulf teams.

In the underworld it’s even more entangled: India’s ◯◯◯ is linked with ✗✗✗’s △△, and films are ■■■■ because ✗✗✗, and so on…

Saito:

Whoa—put that in print and we’re dead, right?

Sato:

Dead. Both of us.

Saito:

Guess we’re dead, huh.

Jini:

How about Pakistan’s domestic market and industry? Japanese FGC folks remember the 2019 surge of Pakistani Tekken players, but we hear little about development and the broader industry.

Pakistani Tekken star Arslan Ash winning back-to-back EVO titles

Sato:

Like India, it’s a mobile-first market, heavily skewed toward cricket titles. The economy leaves a large informal sector, and many seek work abroad. As a sales target, it’s not very attractive.

Development capability is still nascent. I know the associations well; compared to India, there are fewer homegrown titles. Pakistan birthed the software behind the first PC virus (“Brain”), so there’s talent—but it hasn’t yet spread fully into game dev.

Jini:

To the west of Pakistan lie two neighboring countries—Afghanistan and Iran.

Afghanistan has recently drawn attention after the Taliban seized power, while Iran often makes international headlines due to U.S. sanctions and its tensions with Israel.

But what about games in these countries?

(Afghanistan map via Wikimedia Commons.)

Sato:

Afghans are into PUBG too—but not via official channels. The informal market dominates, so formal exporting is tough. Linguistically, though, it connects to Iran; Persian releases can reach users in Afghanistan and Tajikistan.

(Iran map via Wikimedia Commons.)

Sato:

Iran’s situation is difficult, but people still play. A local distributor once told me “Grand Theft Auto is banned here.” I asked, “So what’s popular?” “Grand Theft Auto,” he said.

Iran has its own third-party app stores. Some foreign companies quietly sell games there through those platforms despite sanctions. I can’t name names.

Saito:

(How do you even know that… are you a spy?)

Sato:

I’m not. I just get asked that everywhere.

Saito:

He read my mind.

Sato:

In any case, U.S. sanctions will likely persist. There are many fans and a local ratings system, but it remains a very difficult market. I wouldn’t recommend it.

Jini:

Central Asia usually refers to Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan—former Soviet republics. Forgive me, but surely there’s hardly a game industry here…?

Sato:

On the contrary—hugely important. These countries are poised to become key players in development.

Jini:

In development? They’ve been invisible till now.

Sato:

They were in Russia, doing the work you didn’t see. One of Yandex’s founders is Kazakh, for instance. Many Central Asian talents went to Russia—but with the war in Ukraine and a suffocated export market for PC/mobile games, they’re returning.

Now Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are launching game incubators and accelerators one after another.

Jini:

So the Kazakh and Uzbek governments see opportunity and are backing independence?

Sato:

Ministers show up at dev events—support is active. But it’s not just local governments: in Kazakhstan, Turkey’s WN Media Group is involved; in Uzbekistan, Germany’s Goethe-Institut.

As Russia’s influence wanes, Europe and China are investing to expand cultural reach.

Call it a “cultural Great Game” unfolding under the shadow of the real war—odd, but it’s nurturing Central Asian devs. Some Russian developers are even relocating to Kazakhstan.

(Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan. Sourced from Wikimedia Commons. )

Jini:

So: Russia’s invasion and the resulting sanctions.

Sato:

Boycotts and sanctions bite hard—down to payment rails. Not being able to sell abroad is brutal, hence moving companies next door.

Devs once came to Russia because the work was there; even if your own game didn’t sell, Western outsourcing kept studios afloat. The war blew that hope apart.

Moscow is funding “propaganda games” to stem brain drain, but outcomes are unclear.

Jini:

What will games from Central Asia feel like? For Japanese readers this content is a blank slate.

Sato:

Every nation has its storytelling traditions. Central Asia has a long literary and poetic heritage.

Kyrgyzstan’s Manas, longer than Homer, tells of a hero’s fight against foes from the east.

(Kyrgyzstan’s epic poem “Manas”)

Sato:

In Soviet times, such lore was co-opted: bards were funded to sing the “virtues” of Lenin and Stalin through their own histories—propaganda, yes, but it kept traditions alive.

(‘Rooten’ — horror adventure by Kyrgyz studio Amortiz )

Sato:

There are already attempts to weave local traditions into original games.

About five years ago, a Kazakh studio tried an MMORPG based on Kazakh mythology. It was canceled mid-dev, but I’d love to see such challenges resume.

Jini:

They have the technology, a deep tradition of storytelling, and a strong will to create games that reflect their own culture and history — all the right conditions are in place.

Sato:

That’s why I’m bullish. There’s oil and gas, solid economies, and in Kazakhstan, robust education.

A Central Asia Game Show is slated in Kyrgyzstan; I plan to attend and get a close look at the scene as devs gather from across the region.

(Central Asia Game Show. From the official site.)

Jini:

Now to West Asia—the Middle East. With Saudi Arabia at the center, it’s one of the hottest regions in gaming.

Sato:

“Middle East” spans Arab states, Iran, Turkey, Israel—and sometimes the Caucasus (Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia). Linguistically it’s diverse: Arabic (Afro-Asiatic), Persian (Indo-European), Turkish (Turkic).

Where shall we start?

(Turkey map via Wikimedia Commons.)

Jini:

We touched on Iran earlier—how about Turkey? What’s your take?

Sato:

For Westerners, Turkey used to be the most “legible” Middle East—close to Europe, a NATO member.

Jini:

“Used to be”?

Sato:

Lately it’s grown unpredictable. In game regulation, Turkey can be harsher than Saudi Arabia.

Rules appear out of nowhere—remember the “Minecraft is violent” fuss (※)? There’s little clarity; the Interior Ministry oversees games, but detailed guidelines are lacking.

Saudi, by contrast, issues clear criteria (e.g., what level of skin exposure is acceptable).

Turkey, on the other hand, has ended up in a situation where everything depends on the government’s whim. It used to feel somewhat aligned with Europe, but now it’s become the hardest country to read.

Jini:

Turkey’s known for hyper-casuals. What’s the state now?

(‘Toy Blast’ by Peak Games — a flagship Turkish casual )

Sato:

Hyper-casuals dominated, but tides are turning. With shifts in the ad ecosystem and inflation, CPAs are up; monetizing is harder.

At a recent Istanbul event, Turkish investors said: “The future is premium buy-to-play”—including PC via Steam.

Similar to Korea’s pivot, but driven by strain on F2P ad models—so studios are shifting away from reliance on ads.

Jini:

Come to think of it, Turkey has the acclaimed PC game “Mount & Blade,” doesn’t it?

Sato:

Turkey has a solid economy, domestic demand, and strong technical capability—the conditions are in place.

The “Mount & Blade” series was created by a Turkish startup, and the mobile online giant Peak has also succeeded in Western markets. There have long been many people of Turkish descent in Germany, too, so in that sense Turkey is a country that can adapt to a European model when it wants to.

I wouldn’t be surprised if, five years from now, several Turkish titles emerge that are on par with European ones.

(Mount & Blade II: Bannerlord)

Jini:

True—Ata, the director of “Suzerain” whom we interviewed, is Turkish-German. As a market, though, how does Turkey look? The population is about 85 million.

Sato:

In simple terms, as a market it’s smaller than the Arab world. The Arab world encompasses the deep pockets of the Middle East and the vast population of North Africa, so it’s not really comparable.

In the past, Turkey and Egypt were the two giants of the online-game market—Korea’s “Knight Online” was hugely popular there. But as other countries’ markets have grown, Turkey’s relative presence has declined. Saudi Arabia’s population is also growing, and that trend will likely accelerate.

So that’s Turkey in a nutshell: “the market is in retreat, but the future of development is bright.

(Saudi Arabia map via Wikimedia Commons.)

Jini:

Finally, the Gulf states—since we’re running short on time, although I had hoped to ask about the Caucasus as well, let’s narrow our focus to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. You have connections with Saudi Arabia, and you’ve already given talks in Japan and written several articles about it. Could you once again tell us about the current situation there?

Sato:

It’s undergoing the biggest change. This is the key point.

In 2016, Saudi Arabia launched Vision 2030, a reform plan aimed at diversifying beyond oil. It followed up in 2022 by announcing the National Gaming & Esports Strategy.

Previously, regulations were capricious—even the whims of customs officers mattered, making it unclear what was allowed. Compared to chain-heavy UAE, Saudi had many independent stores and suffered from rampant piracy and gray-market imports, making the market tricky.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (now the Prime Minister) streamlined this situation. He set a nationwide strategy, established game rating standards, and eliminated market piracy, leading to the current boom in the Saudi Arabian gaming market.

(Saudi Arabia’s diversification and growth roadmap “Vision 2030”)

Sato:

We must not forget the crucial precursor: the overseas study fund created by the late King Abdullah, which sent large cohorts to the U.S., Europe, Japan, and beyond.

This wasn’t an ordinary scholarship program. It was exceptionally generous—covering tuition and travel through to a degree (※). In Riyadh and other urban centers, it’s not uncommon to find people working at local bookstores who actually hold U.S. university degrees.

The program has shrunk, but its alumni encountered games—a previously unknown culture—abroad and awakened to their potential. They returned home and became the originators of Saudi Arabia’s game industry. They are the people who now anchor the industry’s core.

(※https://grad.uwo.ca/finances/saudi_bureau.html)

Jini:

Saudi Arabia is perceived as restrictive toward women. Has game culture spread among Saudi women too?

Sato:

Absolutely. The Ministry of Communications and IT reports 23.5 million gamers—48% women. Women also make up a significant share of developers.

At a Riyadh accelerator I visited, men and women worked side by side—and many team leads were women.

Saito:

There’s a women-only game event too, right?

Sato:

That’s GCON. As you said, it’s a women-only game event brand that’s been running since 2012, covering everything from development to esports. With support and sponsorship from companies like Nintendo and Sony, it has been gathering fans and developers for years. The event is organized by Ghada Almoqbel, and she is quite impressive herself. Saudi Arabia has the PIF investment fund, which invests in major game companies like Nintendo and Nexon, and its subsidiary, the Savvy Games Group. She was the head of the Saudi game industry report there, making her the most knowledgeable person on the Saudi game scene.

(Ghada Almoqbel https://saudigazette.com.sa/article/624188より)

Sato:

Saudi women are highly entrepreneurial and very capable—that’s the impression I have. University enrollment rates are higher than for men, and there are many women entrepreneurs.

Why is that? Historically, Saudi women spent much of their time at home; to work outside the home—such as in healthcare—they studied extremely hard, and games have long made up a major share of their leisure.

And now, with telework widespread, in IT you can actually start a business without ever stepping outside your home.

Saito:

In a country with a strong legacy of polygamy and patriarchy, women who have survived shrewdly are now using those survival skills to hold up the backbone of industry. That’s remarkable.

Sato:

And in doing so, they’re even changing society.

As recently as seven or eight years ago, Saudi Arabia was a country where building entrances and seating were separated by gender—there were literal partitions. That has changed rapidly.

I’ve heard there are around a thousand women game developers in Saudi today, and I believe it’s women who hold the key to the country’s next generation.

(Gamers8 — a world-class esports festival in Riyadh)

Jini:

How did such rapid change happen in just a few years?

Sato:

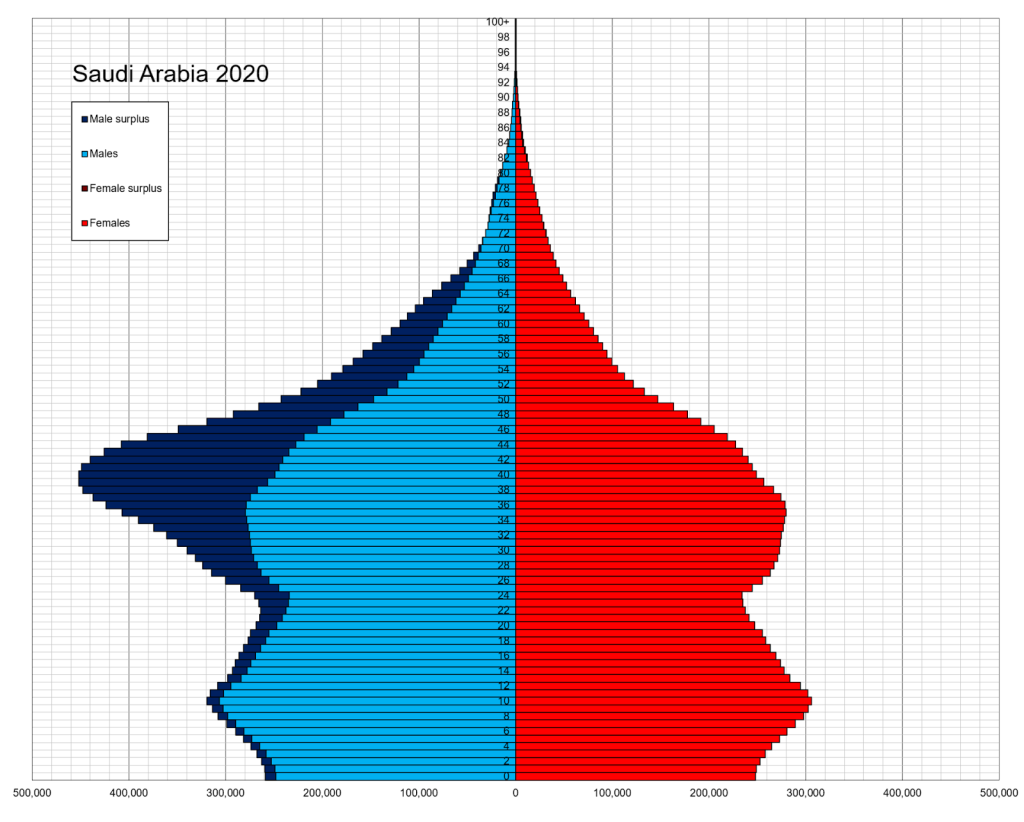

Several factors:

1.Youth demographics—the median age is ~29 (vs. nearly 50 in Japan). Wealth + youth is

a powerful combo.Policy tailwinds—Vision 2030, the national gaming/esports

strategy. Strong centralized push.

2.Industrial strategy—shared national desire to diversify beyond oil.

3.Shifts in social attitudes toward authority (complex to unpack here).

4.Returnee scholars—now conduits for global culture.

(Saudi Arabia’s single-age population pyramid (2020) )

Jini:

And when the young spend discretionary income, they spend it on games—an attractive market indeed.

Sato:

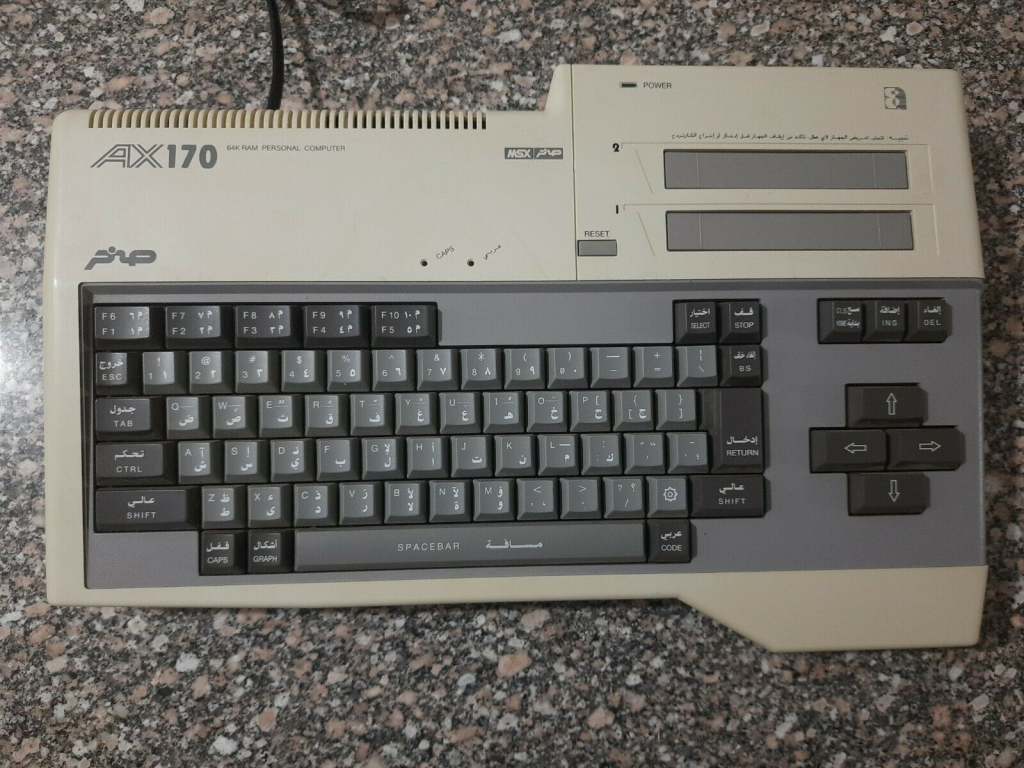

The GCC actually has deeper game roots than many think. In the MSX era, Al Alamiah localized an Arabic MSX—so the cultural base exists.

Given the love of cars and football, racers and soccer titles are strong in Saudi, while other genres mirror Europe. As the industry matures, tastes will likely evolve.

(Sahkr AX-170 by Al Alamiah[Sakhr AX-170/?]. Said to be a localized version for the Arab market of Sanyo’s MPC-2 imported from Japan by the Kuwaiti company Al Alamiah; from eBay.)

Jini:

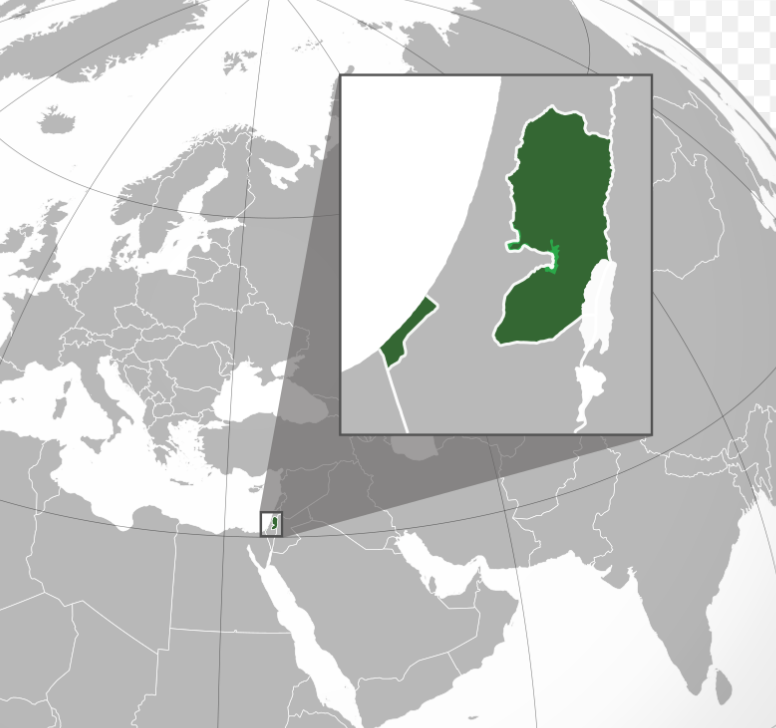

We should also touch on Israel and Palestine, given the ongoing war.

(State of Palestine — orthographic projection)

Sato:

Before the current war, Palestine pursued IT-led development and encouraged outsourcing; IGDA had a Palestine chapter that ran workshops.

Mobile gaming was active then, despite shaky connectivity. Even now there are devs doing 2D/3D action and 3D art outsourcing.

Jordan—where I first worked—has many Palestinians. Rababa Games, led by Hussam, became one of MENA’s notable studios. Their racer HAJWALA (“drift”) was a Saudi-region hit and even has a niche fan base in Japan. It was adapted into films twice, and they’re hard at work on the sequel.

(Israel map via Wikimedia Commons.)

Sato:

Israel’s focus on the IT industry is well known. In games, good indies have begun to pop up here and there—Blind Drive even won an award at the Tokyo Game Show a few years ago. I’m seeing a noticeable number of works that make use of meta interpretations of the game medium. That said, the scene as a whole still isn’t that large.

Where Israel is particularly strong is social casino. That strength is underpinned by proximity to financial centers and a background of being very capable in adtech and in the somewhat gray “toolbar” business.

Do you remember the old toolbar business? The one that would silently install malware-like—indeed, effectively malware—browser toolbars. Two of the biggest players in that space were Israeli companies.

Jini:

That’s… gray.

Saito:

Israeli companies can be hard to get a clear handle on. You often see Israeli founders with a U.S. headquarters; they retain control of the capital and the core tech/know-how and focus only on R&D. In that sense, it’s very “Israeli.”

Sato:

Adtech may be the most “Israeli” line of business: people from the old toolbar companies laid the foundations, staying off the front stage and connecting the dots across the adtech landscape (the so-called “chaos map”) behind the scenes. The country has long had a culture that leans B2B over B2C.

As I mentioned, mobile games in Palestine are inseparable from advertising, which means that if you want to monetize mobile games, you inevitably have to rely on Israelis for adtech.

A Palestinian friend of mine living in Jordan once sighed, “I’d never do business with Israelis… except I have to, for adtech.”

The game industry, too, is not immune to the world’s fraught and tangled geopolitics.

Jini:

Let’s hope peace returns soon—so both peoples can keep making and playing games.

Jini:

Thank you again for your valuable time—and for the even more valuable insights. Today we focused mainly on the appeal of game markets with Asia at the center, but we actually didn’t get to hear about the informal markets you’re strongest in, like Eastern Europe, South America, and Africa. And of course, we would also have liked to hear about North America, Western Europe, and Oceania.

Sato:

No, no—the thanks are all mine.

Right. Today I mostly talked about formal markets, but even in countries where people can’t afford to buy games at official prices, there’s always an informal market. If there’s another opportunity, I’d love to talk about that side as well.

That said, I don’t think of it as anything grand. The simple truth is: in every country, in any slum, games are there, and there are people playing them. Games reach you wherever you are. The only entertainments like that are music and games.

Games really are incredible.

Saito:

For my part, I’m honestly in awe of how you’re plugged into the world’s game scenes, both front and back. It’s almost like you’re a—

Sato:

I’m telling you—I’m not a spy.

Saito:

I know, I know. Talk to you a few times and anyone can tell that’s not your agenda. I’ve never met anyone this straight-up about games.

Jini:

One last thing I really wanted to ask: what, honestly, is your “purpose,” Sato-san? You said at the start you wanted to contribute to Japan’s game industry. But you yourself aren’t an insider at a Japanese game company.

With your abilities, you could just settle in a “high-growth region” and make an easy living.

Sato:

I wonder about that myself sometimes—“I’m doing this for Japan’s game industry, so how did I end up all the way out here?” Seeing game industries flourish overseas, I often feel frustrated about Japan’s current state. But in the end, I just love Japanese games.

Every time I go abroad and touch wonderful game cultures in other countries, that feeling only grows stronger. Games are a global medium. Japan’s game culture is a part of the world’s game culture—and as someone raised on Japanese games, I, too, can be part of that world.

Isn’t that a pretty wonderful thing?

After the commemorative photo session, Saito asked me, “How was it?”

In other words, he was asking for my impressions of Sho Sato as a person.

I was at a loss. How was it? What should I say? I’d never encountered anyone like him.

He spoke for over four hours without a break (we had breaks scheduled, but he talked straight through them), every topic brimming with marvels and all interlinked. Without time constraints, he could have kept going until morning.

And fast. Unstoppable. People generally speak about 15,000–20,000 characters’ worth per hour; when we transcribed the interview later, it came to 110,000 characters over four hours—27,000 characters per hour. That figure includes the interviewer’s turns—astonishing.

There are no words for something you see for the first time.

I finally managed, “He could probably write three paperbacks just from what he said today.” Saito laughed.

“Make it ten. And if you don’t limit the topics, ten times that.”

Ten times ten is a hundred. It sounded like a joke, but I couldn’t take it as one. If anything, Sato felt bottomless enough that even a hundred wouldn’t be enough.

Surveying the scene like the calm after a typhoon, I felt I finally understood why Sato, who says he loves Japanese games, spends his days crisscrossing the globe. That explosive energy can’t be contained within Japan alone. To absorb the heat of this singular talent, Sho Sato, you’d need the Earth’s full 510 million square kilometers of ground.

To see everything, to know everything—that’s a desire that has driven humans since antiquity, yet we’re also lazy animals who at some point give it up as impossible. But there are those, rare few, who genuinely try to carry it out. In one era, that undertaking was called Enlightenment.

Travel is the act of expanding the bounds of the world you can comprehend. Sato’s research reports invite even those of us merely listening from our seats onto that journey, letting us glimpse new vistas and possibilities.

Where will he take us next?

Sho Sato will keep on freely soaring across the world, wherever it leads him.