Share

https://int-magazine.com/interview/cult-of-the-lambs-julian-wilton/

クリップボードにコピーしました

Interview #10 2025.10.27

Cult of the Lamb’s chaotic humor, cute visuals, varied gameplay, and happy characters reflect the personality of its creator.

Last year, the INT editorial team attended PAX AUS – Australia’s biggest gaming event – and mingled with its attendees. Unlike Japan’s Tokyo Game Show, where major companies dominate the exhibition floor, PAX AUS is lined with several quirky indie booths. At the center of it all, drawing the largest “congregation,” was the Cult of the Lamb booth.

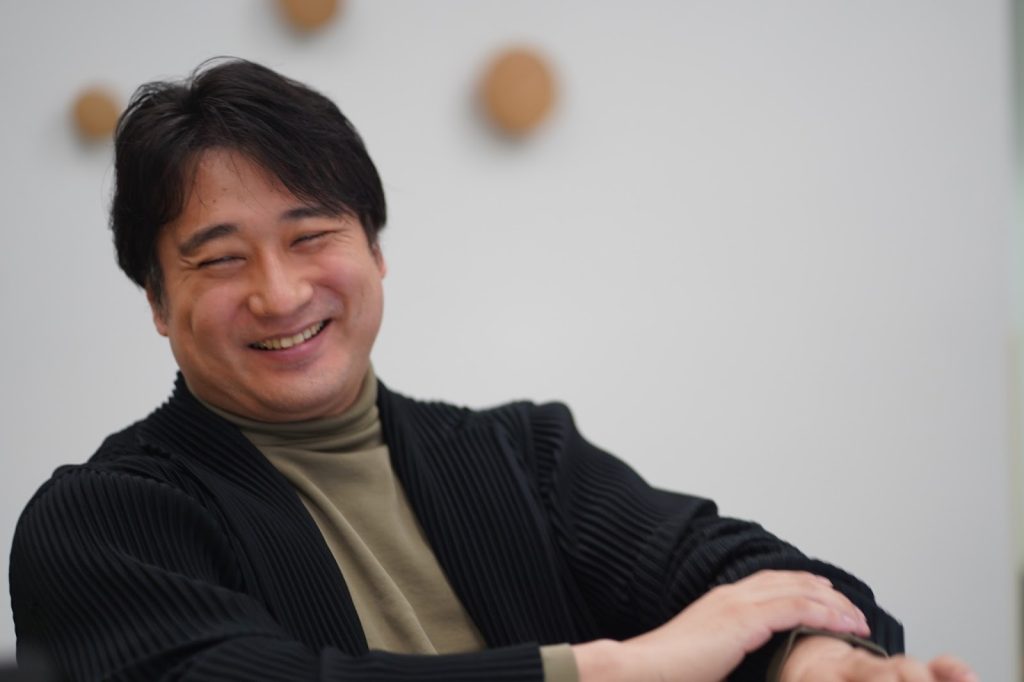

Cult of the Lambs’s fandom radiates the same sense of unity that the game’s cults exude. Just what kind of studio creates a game so mischievous yet so heartwarming? The INT team requested an interview with Julian Wilton, co-founder of Massive Monster and Creative Director on Cult of the Lamb, to see what goes into making such a sadistic yet loveable hit.

Questions, Planning, Editing /Jini

Interviewer /Daichi Saito

Author /Shu Chiba

Photographer /Akihiko Iyoda

Saito:

I finished Cult of the Lamb. Honestly, it’s a major achievement – not for me, but for you. You made a game that even someone like me, who isn’t good at action games, could play to the very end. I felt a real sense of accomplishment when I finished it.

Wilton:

What difficulty did you play on?

Saito:

I think “Normal”. The default one.

Wilton:

Then we’re already friends. See, I’m not good at action games either. I designed Normal difficulty to be something that I could actually beat. Internally, we jokingly called it “Julian Mode.” So really, the Normal mode of Cult of the Lamb was made for me.

Saito:

To be honest, I never felt like we were strangers. You come from an Adobe Flash game background, right? I used to be into Flash and other free format games too. When I joined Dwango, I got involved in organizing the “Niconico Indie Game Festival,” a contest for free games.

Wilton:

Ah, that vibe: young amateurs making and playing games. I know exactly what you mean. As a kid, I was all about free games.

Do you know RuneScape? That old MMORPG that launched around 2001 and is still going strong? I was totally hooked on it in grade school.

It had a paid membership that cost around $12 a month. I wanted it, of course, but there was no way my allowance would cover it. One day, I saw a 24-pack of Coke being sold for $12. At school, a single can would go for about $1.50. That’s when I came up with a strategy. I split the pack and sold individual cans to my classmates for a dollar each. And guess what? The difference added up to…

Saito:

$12. Enough to buy that membership.

Wilton:

Exactly. Pretty sweet business, right? But free-to-play online games always find ways to push you toward spending more. After the membership, I wanted items that cost real money, too. But you can only flip Coke for so long. So this time, I started hustling in-game.

(RuneScape has been running for nearly 25 years. The image above is from the “Old School” version of the game, which recreates its early low-poly look.)

Saito:

Were you reselling in-game items or something?

Wilton:

That wouldn’t get you very far. If you wanted to make money in an MMORPG, you would have to scam people. In my case, I used the in-game dice mechanic to run a gambling scam. I’d offer to host dice games for other players. At first, I’d run things fairly, just like any proper bookie. But once the stakes got high and someone handed over a big bet, I would vanish by logging out – taking the money with me in the process.

That was a classic scam. It used to happen all the time in online games. With the in-game currency I swindled, I bought the items I wanted. It felt amazing. I ended up getting banned—not for the scam itself, oddly enough, but for something unrelated.

Saito:

Ha! You’re a real hustler. I’ve interviewed a lot of game developers, but this is the first time I’ve met someone who used to be a scammer and ran gambling scams in MMOs.

Wilton:

In real life, I was a good kid! Or, well, maybe not? Once I got into high school, I started Googling all sorts of sketchy tech tricks, such as sending viruses to people, hacking into the school network, and disconnecting all the computers. That’s about it, really. I was totally a good kid.

Saito:

Nope, not even close!

Wilton:

What can I say? Watching teachers freak out mid-lesson was hilarious. I don’t do that stuff anymore, of course. Still, that hacker mindset I had as a punk kid definitely carried over into game development.

At some point, I realized that tweaking parameters in a game’s source files could actually change the game itself. It was like peeking behind the curtain. I could rewrite the game however I wanted. My reasoning was that if I could rewrite an existing game’s code, then making a game from scratch couldn’t be that hard. So I hyped myself up and started working on my first game with some friends. That was my first attempt at game development.

Saito:

What kind of game was it?

Wilton:

It never got finished. My friends got bored and left the project pretty quickly.But I decided then and there that I wanted to pursue game development seriously.

I started trying to learn C++. But that language is not user-friendly, so I was totally in over my head. Just as I was about to give up, I discovered Adobe Flash. The art and animation style of Flash games at the time really resonated with me. I gathered a team online and dove into Flash game development. I did the art and animation, and the others handled the programming.

Saito:

You were still in your teens, right? So you already had a creative drive at that age.

Wilton:

Nah, I just wanted pocket money. My mom wasn’t the kind to hand out much allowance, but like any kid, I had things I wanted and stuff I didn’t want to miss out on. Selling Coke one by one wasn’t cutting it.

That’s where Flash games came in. Back then, if a Flash game became popular, it could attract sponsors or even get support from well-known portals like Kongregate or Newgrounds. To me, making Flash games looked like the perfect way to earn some extra cash. That’s probably the reason why I have a hard time seeing my games as “art” in a serious way.

Saito:

But it’s great that free game creators were actually getting some of the profits.

(One of Massive Monster’s Flash-era titles, Angry Bees. Even then, the studio’s graphic style was already well-established.)

Wilton:

There was one game where we made about 1,600 AUD, which was something like 120,000 to 140,000 yen at the time. For us 18-year-olds, that was a mind-blowing amount of money. But beyond the cash, Flash game development gave me something even more valuable:my future business partners, Jay Armstrong and James Beeman, who would go on to co-found Massive Monster with me.

Saito:

They’re both British, right? How did you meet them?

Wilton:

I first connected with Jay online, and together we made a game called Super Adventure Pals. James liked Super Adventure Pals and showed up at Jay’s place with some beer. Jay introduced him to me, and we hit it off right away. Just like that, we were best friends.

(Super Adventure Pals was later remade as The Adventure Pals.)

Saito:

You know, there are other indie devs who came from Flash backgrounds, like Edmund McMillen of Super Meat Boy. Japan also has some iconic Flash games like Sushi Da, but no one to my knowledge has reached your level of success.

Wilton:

We’re rare, even on a global scale. Most of the people I made Flash games with have since quit. The ones who are still around mostly moved on to mobile or HTML5. You don’t see many people who are seriously making games for PC or consoles anymore. It’s a whole different scene.

Saito:

Are there any lessons from your Flash days that still influence how you develop games today?

Wilton:

Definitely the sense of speed. In Flash, when you make a tweak or adjustment, the changes show up instantly. That makes it easy to keep experimenting and respond quickly to user feedback. I also learned a lot about release-update cycles from that.

Another benefit is the ability to rapidly prototype ideas. You can test a huge volume of concepts at lightning speed, and that often leads to innovative mechanics. That’s where I got my motto: “Don’t get too attached to any one idea.”

Saito:

So why did you transition from Flash games to standalone indie titles?

Wilton:

To put it simply, the Flash industry died.

The biggest factor was the rise of mobile gaming. By the mid-2010s, people were playing games on their smartphones instead of in PC browsers. Naturally, the market and potential investments followed that trend. What really killed Flash was the software platform getting blocked on the iPhone. That shut off a massive portion of the market and spelled the end of Flash’s future. So we had no choice but to pivot to PC and consoles.

But we were total nobodies. We didn’t have the resources to just jump into those platforms. We had to work on mobile games and contract gigs to save up enough money to fund a proper PC title.

Saito:

That’s rough. I’ve had my own share of side jobs when my company was in trouble, so I get it. But wasn’t it hard to see all your Flash-era success just wiped clean?

Wilton:

Actually, our Flash background helped us take that next step. One of the big Flash portals back in the day, Armor Games, started moving into PC publishing. They were facing the same extinction-level event as we were. So they tried to survive by leveraging their network and Flash expertise. Armor Games started porting major Flash titles like Chibi Knight and GemCraft to PC. Since we’d already worked with them on Super Adventure Pals, they reached out to us. That was right around the time we were forming Massive Monster.

In 2018, we released our debut title under the Massive Monster name: The Adventure Pals. It ended up earning about 1 million AUD in total. For a debut title from a team of unknowns, that was a pretty solid result. The following year, we released our second game, Never Give Up. By then, I think Armor Games had pretty much shifted entirely into publishing.

(Armor Games has shifted from a Flash portal to an HTML5 game site and now publishes titles on Steam and other digital platforms.)

Saito:

So Armor Games were your comrades in escaping the sinking Flash ship. But why switch to Devolver Digital for Cult of the Lamb, your third title?

Wilton:

You’re seriously asking me that? Come on. It’s Devolver Digital! I don’t know how they’re perceived in Japan, but in the indie world, Devolver Digital is the dream. They’re the top of the top. When they come calling, you don’t say “no.”

Besides, things were financially tight with Armor Games. The funding we got from them was very little. On top of that, there were recoup contracts and all sorts of limitations. Looking back, I think the hourly wages we earned on Never Give Up and The Adventure Pals were probably below minimum wage. But the relationship held because we were all rookies in the industry. None of us really knew what was fair or standard. These days, Armor Games has matured. It now has several hit titles under its belt and offers much better working conditions, I’m sure. We all grew up, I guess.

Saito:

So how did you actually get in touch with Devolver Digital?

Wilton:

We took a pretty unorthodox route. In 2018, Jay, who lives in the UK, received a BAFTA Breakthrough Brit award for his work on The Adventure Pals. It’s an award recognizing promising young British creatives in entertainment. As luck would have it, someone from Devolver Digital happened to be there. Jay got to talking with them…

Saito:

…And they hit it off? Did Jay get invited to pitch a game?

Wilton:

We got a name.

Saito:

A name? That’s it?

Wilton:

Yep. From there, we guessed what their email might be—based on the name and Devolver Digital’s domain—and sent a cold email with our pitch and prototype. And… it got through.

Saito:

It actually reached them?

Wilton:

Yep. Not long after, that person called us and asked, “How much funding do you want?” We were super nervous, of course. But we weren’t about to back down just because it was Devolver Digital. So we went all in and asked for $300,000 U.S. dollars, not Aussie. That was way more than we ever got from Armor Games.

He said, “Nope. That won’t cut it.” “$300k is chump change. You’ll need way more than that. We’ll cover it.”

Saito:

That’s… ridiculously cool. As a publisher myself, that’s the kind of line I’d love to say someday.

Wilton:

Of course, we were pitching to other publishers at the time, too. But come on.We were just three unknowns. No one else gave us a real shot. The most encouraging response we got was along the lines of, “Interesting idea, but could you make it on a tighter budget?” So yeah, when Devolver Digital came through with their offer, we were pumped. And it wasn’t just about the money.The rest of the terms were great too.

But that kind of support comes with pressure. We weren’t just expected to deliver on quality. We had to deliver on the business side, too. At our first pitch, we said we planned to release two major updates within six months of launch. That way, even if the initial release underperformed, we could attract new players through those updates and recoup development costs over time. Devolver Digital liked that plan. They said, “You guys get how to make money.” But they also warned us. “Good strategy, but it’ll take way more time and money than you think.” They were absolutely right. Total pros.

Anyway, once we had the funding locked in, we built our production schedule around it and set clear milestones together with Devolver Digital, working side by side.

(A prototype of Cult of the Lamb.)

Saito:

It’s great when devs and publishers are that in sync. But I’m guessing that a big-name publisher like Devolver Digital also wants to have a say in things, right? They’re known for having high standards, after all.

Wilton:

That’s what we expected too. But that wasn’t the case. At least with us, they were super hands-off. If we asked, they gave advice. But they never interfered with development. The only things they really pushed were marketing strategies around launch and Twitch integration features.

Saito:

That’s amazing. This kind of developer-publisher harmony is what indie dreams are made of.

Wilton:

Well, things weren’t actually going that smoothly. At least, not from the outside.

To be blunt, Cult of the Lamb was a steaming pile of crap up until about nine months before release. It was rough.

Just to defend the team here: this wasn’t a lack of development skill. Cult of the Lamb is a systems-driven game. With this kind of title, you gradually stack up systems and mechanics through repeated gameplay loops. Eventually, if everything clicks, it hits a critical mass and explodes.

(Wilton gestures with his hands opening outward) Boom.

Saito:

(Mimicking the gesture) The fun just goes boom.

Wilton:

The worst part was that even we developers couldn’t confidently say, “This is gonna be great!” I was scared stiff. And Devolver Digital must have been freaking out, too. The launch date was fast approaching. The game? Still crap. Daichi, if you were the publisher in that situation, what would you say?

Saito:

I’d be losing my mind.

Wilton:

Same. But Devolver Digital? They just smiled and watched.

That silent pressure scared the hell out of us. We pushed harder than ever; building up the systems piece by piece. Then one day, I started my usual test play session (I’d already done thousands by then). Normally, I’d last 30 minutes, maybe a couple hours tops before getting bored. But that day, I just didn’t stop. I kept playing. Hours went by. By the time I looked up, the sun was setting.

That was it. The boom moment.

Saito:

You mentioned earlier that Devolver Digital is every developer’s dream. As a publisher myself, I feel the same way. They serve as both rivals and role models. That said, some of my publisher friends have voiced their concerns. They wonder if Devolver Digital might lose its distinctive brand identity as it grows. What do you think?

Wilton:

One time I spoke with Devolver Digital’s CEO, and he said that a Devolver game needs to give you that “hair-standing-on-end” kind of thrill. The kind we all felt when we played Hotline Miami or Inscryption. And the truth is, Devolver Digital has an incredible nose for finding those kinds of electrifying games and devs. (That includes us!)

But here’s the catch: that kind of emotional impact can’t be quantified. And things that can’t be measured don’t impress investors. When a game flops, they’ll say, “Why didn’t it sell? Do the analysis. Make something that will.” To some extent, that’s fair.

I think Devolver right now is trying to strike a balance between commercial viability and their signature cool, artistic edge.

Saito:

That might actually reflect a broader maturity across the entire indie game scene.

(Artwork used in Devolver Digital’s 2024 Steam publisher sale. Cult of the Lamb was featured as a flagship title alongside hits like Enter the Gungeon and Hotline Miami.)

Saito:

So, I gotta admit… I love poop. 💩

Wilton:

That’s disturbing. But I won’t abandon you. We’re friends, after all.

Saito:

Wait! No. That must have been a translation error.

I meant in Cult of the Lamb! The humor is so bold. Like how the followers just crap all over the camp, and the little lamb leader has to clean it all up. Some followers love poop. One even asks you to feed poop to another follower. Julian, be honest.Do you like poop?

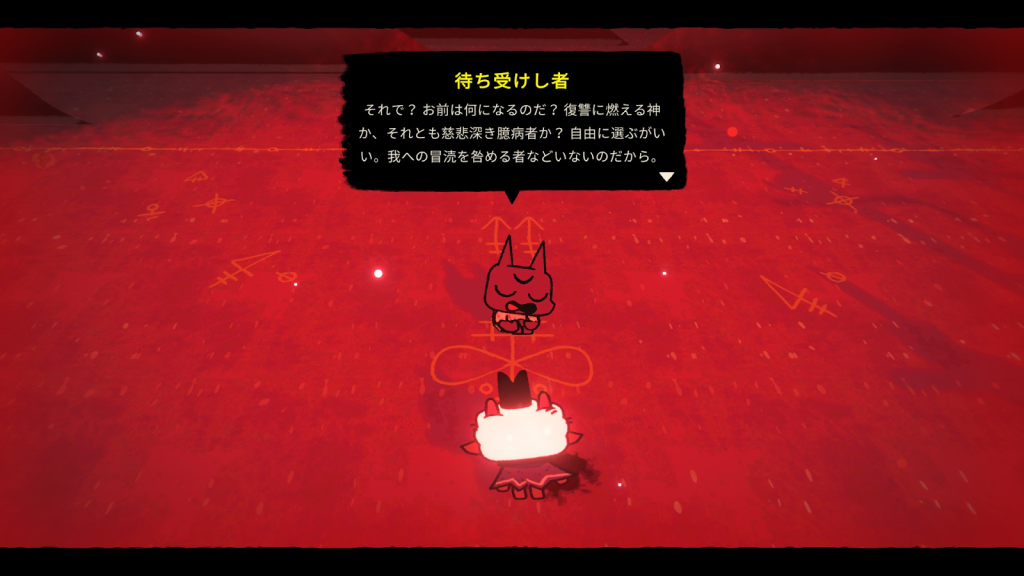

(A quest where you make another follower eat poop. Refusing lowers their Faith.)

Wilton:

Not particularly. I’m not that into gross-out humor.

Saito:

You totally just pulled the rug out from under me.

Wilton:

Sorry! We weren’t planning to include much crude humor at the start. The original direction was grim and mature – sort of like Darkest Dungeon. But that genre is oversaturated, so I suggested we add humor to differentiate ourselves. That’s when Harrison Gibbins, our lead programmer, really got into the poop jokes. The poop dishes in the game? I’m pretty sure those were his idea.

Personally, I don’t mind cheap laughs.That includes toilet humor. But I think humor without context doesn’t work. In Cult of the Lamb, for instance, there’s a gag where you trip out after eating mushrooms. But that joke is rooted in real-life cult rituals, right? There’s a reason behind it. It adds to the immersion. On the other hand, if a joke feels totally out of place, it breaks immersion. That’s no good. From that perspective, even the poop jokes have context. It’s like Tamagotchi.

Saito:

Tamagotchi? That’s unexpected.

Wilton:

One of the core pillars of Cult of the Lamb’s design is the followers. If players feel attached to their followers, they’ll feel attached to the game. So how do we make them lovable? That’s when I thought ”What if we treat followers like digital pets, like Tamagotchi?”

In Tamagotchi, you have to care for your pet in every way—from treating illnesses to cleaning up their poop. It’s tedious, but through that care, you naturally develop affection. It’s like raising a kid. The fact that Tamagotchi is so well-known also helps. Everyone is familiar with its mechanics. We don’t have to explain that leaving poop around will lead to sickness. Players just get it.

(Tamagotchi.)

Saito:

That’s very much in line with that late-90s to early-2000s vibe. It’s the same kind of tone we saw in a lot of Flash games.

Wilton:

The culture around the early 2010s was another big influence. In terms of games, I’d say Castle Crashers’s crude humor had a huge impact. There were also cartoons like Adventure Time, Gravity Falls, and Over the Garden Wall. Those cartoons were wild and chaotic, but they would occasionally take serious turns. That contrast stuck with me.

When we were making The Adventure Pals, we were so influenced by that era of animation that we packed in gag after gag. But that backfired.People saw it as a kids’ game. The thing is, Steam’s core demographic consists of people in their 20s and older. Once your game gets labeled as “for kids,” it drastically narrows your audience. So with Cult of the Lamb, we tried to keep the fun tone but present it as a more mature game that could appeal to the Steam crowd.

(Poop piling up in the village. If you don’t clean it up, disease will spread.)

Saito:

That middle ground of not being too childish and not too mature is what makes Cult of the Lambwork so well. Would you say that balance reflects your authorship as a creator?

Wilton:

Yeah, I think a creator’s ideal “authorship” is when their personality naturally emerges through gameplay. When someone who knows me plays one of my games and says, “This feels just like you,” I feel like I got complimented. That’s why we at Massive Monster pack in everything we love into our games.

For us, authorship means making things that are accessible to everyone. Games that are easy to understand, colorful, and fun to play. When you combine that with our personalities, you get something truly ours. That’s the identity we decided on when we founded Massive Monster.

Saito:

That explains all the parody references in Cult of the Lamb.

Wilton:

Yeah, stuff like Midsommar, Suspiria, Eyes Wide Shut – we threw in references to all our favorite cult and occult films.

Saito:

Interesting choice. In most of those movies, cults aren’t exactly portrayed in a positive light. In general fiction cults are usually seen as scary or evil. But your game makes it fun.

Wilton:

Well, come on.Being a cult leader looks fun, doesn’t it? Don’t you wanna be one?

Saito:

I totally do.

Wilton:

The original prototype was much simpler in that all you did was recruit allies and build a village. But after Never Give Up didn’t do well commercially, we needed a hook.Something with stronger marketing potential. That’s when the cult idea came up. The desire to influence others is a hidden fantasy that everyone has. Being a cult leader is a classic player fantasy. It’s a unique premise that taps into something primal.

(An illustration of the player fantasy: “I want to be the leader of a cult.”)

Saito:

And the fact that the cult leader is an adorable little lamb just makes it all the more compelling. This cute face doing increasingly dark stuff.It’s a brilliant hook.

Wilton:

Exactly. Lambs are symbols of purity. The followers have those big round eyes too.They all look very innocent.

When you play the game, those characters do some pretty twisted things. That contrast creates a clear and surprising gap that makes people want to talk about it. This word-of-mouth leads more people to want to try out Cult of the Lamb. If everything in the game had been dark from the start, I don’t think it would’ve gone viral. A dark, serious cult game isn’t surprising; it’s predictable.

Saito:

Just being cute wouldn’t have done it either. With Cult of the Lamb, players get to wield power through a cute avatar. That softens the blow of their actions. Even when you’re performing sacrifices, it somehow feels okay.It’s like the game is whispering, “It’s fine, just go ahead and kill them.”

Wilton:

We actually built a mechanic where there is always at least one annoying follower in your cult. That way, no matter who’s playing, there’s someone players will want to sacrifice.

Saito:

But even then, you still feel guilty when you go through with it.

Wilton:

We made the followers smile when they’re chosen for sacrifice. It’s like they’re happy to give up their lives. That balances the tone and makes it easier for the player to exercise their power.

“Followers” and “power” are the two main pillars of Cult of the Lamb. Even if you want to be a good cult leader, the game constantly tempts you to wield power in an evil way. For example: if you die, you can resurrect by sacrificing a follower. The mechanics themselves gently nudge you toward evil.

(The sacrifices necessary for the cult’s survival.)

Saito:

I’m starting to feel like the game’s systems are the real dark masterminds here.

Wilton:

The power mechanics built into the game echo the true nature of cults.

Most cults start out with good intentions. But as the group grows and their influence expands, the leadership starts to abuse their power. We wanted players to experience that progression themselves.

Saito:

Coming from Japan, where real-life cults have executed terrorist attacks, that hits especially hard.

Wilton:

We do give players choices. Whether you want to abuse your power or not is always up to you. Every decision you make stacks up and in the end, we want players to ask themselves, “Am I a good person or a bad one?” That’s how they come to understand themselves.

Saito:

When I talk to Western developers, I often hear them emphasize “agency”—the ability to make meaningful choices. Would you say that’s important to you too?

Wilton:

Absolutely. Players should always feel like they are choosing freely and acting with intent. Even if their options are limited, the feeling of agency is crucial. For me, it’s more about that emotional experience than actual system complexity.

(What kind of cult leader you become is up to you.)

Saito:

There’s also this dark humor in those moments of power. Like when you sacrifice one follower and another runs up and goes, “Why did you kill them?!” It’s bleak but kind of hilarious.

In a game as repetitive as Cult of the Lamb, those little narrative beats keep things fresh.

Wilton:

Exactly. Repetitive loops need freshness. You have to keep delivering unexpected moments to maintain dopamine flow. Humor is one of those surprises. It’s something players don’t anticipate but find delightful. Since the dungeon sections can get pretty dark and serious, coming back to the village and seeing ridiculous stuff happen makes the contrast even funnier.

Saito:

Cult of the Lamb blends a ton of genres—colony builder, hack-and-slash, roguelike—and it all works seamlessly. What made you decide to go for that genre mix?

Wilton:

We thought it’d be cool to have a gameplay loop where you go back and forth between dungeon crawling and colony building. The idea was inspired by Stardew Valley’s mining combat. We wanted to expand on Concerned Ape’s work. Moonlighter’s constant shifting between shopping and dungeon crawling also provided inspiration for Cult of the Lamb’s unique gameplay loops.

If you mash together popular genres and cherry-pick the best parts, it’s bound to hit. Simple math, really.

(Moonlighter)

Saito:

Easy for you to say. Tons of games have tried to do what Cult of the Lamb does and usually end up becoming bland and mediocre. I think Cult of the Lamb succeeded because it combines all those genres and kept things accessible to everyone.

Wilton:

Exactly. That’s something we take real pride in.

My game design philosophy is: “Never make a game that excludes players.” That’s something I apply to everything we make. Because if the game’s too hard, then I can’t play it!

I’m genuinely terrible at action games. I played Cult of the Lamb’s Normal mode over and over until I could beat it. And I know I’m not alone. There are tons of people out there who aren’t good at games but still want to enjoy them. If we create something fun, I want everyone to be able to play it.

Saito:

So that’s why Normal mode is called “Julian Mode.” I guess I was one of many “Julians” who beat it.

Wilton:

Actually, you’re better than me. I couldn’t even beat the final boss on Normal!

That said, combining popular genres doesn’t always constitute a win. Each genre has its own fanbase, and they all expect different things. That’s especially true when it comes to difficulty.

Dungeon crawler fans, for example, tend to expect hardcore challenges. Even now, we get a lot of complaints from players saying the game is “too easy.” But that’s just a side effect of trying to satisfy a broader audience that includes non-gamers.

Saito:

I’m not great at difficult games either. But as you said, I still want to enjoy games. The thing is, casual games don’t really scratch that itch. I want to feel like the game challenges me.For that, I need something that feels like a “real” game.

Wilton:

Yeah, if it’s too easy, it starts to feel patronizing. That balance is tricky.

Here’s a little secret: Cult of the Lamb has an automatic difficulty adjustment system.

We monitor player behavior. If someone seems unfamiliar with the game, or clearly struggles with combat, we give them invisible assists. Say an inexperienced player almost dodges an attack. We might secretly make their character’s hitbox smaller so as not to get hit. That way, even if someone fails repeatedly, they don’t lose confidence.

That system only kicks in on the lower difficulty levels, though. If you pick a higher setting, it won’t help you.

Saito:

People often equate low difficulty with laziness, but designing an easy game takes just as much effort as a hard one, if not more.

Wilton:

That same design philosophy of “don’t exclude anyone” applies beyond gameplay.

Early in development, Cult of the Lamb had a pretty convoluted theme and story. The idea was that the protagonist was a forgotten god who had lost their followers and was trying to regain their place in the divine hierarchy. I think we even had them flying around on a whale or something. It wasn’t a bad idea, but it was hard to digest. There was just too much to explain and players couldn’t get a clear image right away. Good design is something anyone can grasp instantly.

Saito:

That clarity runs through the whole game.There’s no stumbling over mechanics.

Wilton:

We always try to design things so players can learn intuitively. Even in the tutorial, we didn’t want to dump a bunch of info all at once. At first, you can only walk. Then you unlock the ability to attack. Then the ability to dodge. We teach one mechanic at a time.

We call this approach “spoon-feeding,” as it helps players grow accustomed to the game. Cult of the Lamb is built this way. It’s designed so that all its major systems are unlocked slowly in a process that takes up about the first half of the game. It’s a slow, gentle curve.

Saito:

Massive Monster is friendly in real life too, especially with regards to how it manages its community. I heard the studio even helped host a fan wedding at the last PAX AUS?

(A fan-made wedding ceremony.)

Wilton:

PAX is the biggest event in Australia, and it’s always fun engaging with players. I go all out every time, but the company keeps scolding me for it. Even if we say it’s for “brand building,” all that time spent with fans could also be used for game development.

These days, we’ve delegated most of the community management to our community and marketing managers. They’ve done an incredible job. We’ve got such a wonderful community now. Maybe it’s because Cult of the Lamb is about cults, but the game’s community has become very cult-like as a result.

Saito:

Streaming culture is such an important aspect when it comes to building a gaming community. I personally love watching people stream our games. Are you the type to watch people play Massive Monster productions?

Wilton:

Not really. I don’t enjoy watching others play games. Plus, it stresses me out when I see a bug or notice a player looking bored. The parts viewers find funny are often the exact parts that give devs a stomachache.

I do watch other types of fan videos, though. Some have really stuck with me. One was a deep lore theory video that made me go, “Okay, there’s no way the devs thought that far ahead.” But it was so convincing that even I started to believe it.

Saito:

The connections between players are amazing too. The local co-op update you recently released was great.

(From the official teaser for the upcoming co-op mode update.)

Wilton:

Local co-op was something I absolutely wanted to include. Games are just more fun when you play them with someone else. I grew up gaming with friends, so that feeling is really important to me.

Since Cult of the Lamb was originally a single-player game, I didn’t expect co-op to significantly boost sales. But then we ran a 50% off campaign to coincide with the co-op update, and we saw our biggest sales spike ever—two years after launch! Even bigger than the “sex update” we released earlier, which added follower mating mechanics. A pleasant surprise. Turns out, people love friends more than sex.

Saito:

So Cult of the Lamb is a game made for friends. Actually, our Editor-in-Chief helped shape this interview from a critical standpoint, and that was their core hypothesis: that everything—from the approachable gameplay and narrative humor, to the co-op and community support—was made for the sake of cooperative play.

Wilton:

That’s such a great insight. It might sound cliché, but we genuinely worked hard on both the development and marketing to make something people could enjoy cooperatively. We had fun doing it.

I think anyone who’s played Cult of the Lamb gets that.

Saito:

Alright, we’re almost out of time. Can I ask what’s next for you?

Wilton:

We’re working on paid DLC for Cult of the Lamb. After two years of free updates, I think it’s about time we earned a little money off of it. This paid DLC will probably mark the end of major updates for Cult of the Lamb.

We’ve also started working on a new title. It’s still under wraps, but I’m confident our fans will love it. Please look forward to it!

A game’s genre, art style, difficulty, and the studio developing it are just a few factors that people consider when choosing what to play. For instance, a title or franchise that is known for its challenging difficulty can intimidate players who do not have the skills or time to complete them. Conversely, those who are looking for a challenge have a tendency to overlook more casual titles. In this sense, a player’s skill and preferences contribute to what games they experience.

Despite players’ selective natures, Cult of the Lamb tries to appeal to a broad audience in several ways. Its cute art style is juxtaposed by the manipulative and sometimes extremist concepts surrounding cults. The addictive gameplay loops which involve base building and roguelike combat (two genres that couldn’t be more different from each other), ensure that casual and hardcore players will enjoy it. Add in the accessibility features such as the auto-adjusting difficulty and Massive Monster has created a recipe that almost anyone can enjoy.