Share

https://int-magazine.com/interview/hooded-horse-founders-tim-bender-snow-rui/

クリップボードにコピーしました

Interview #11 2025.11.03

While well-established franchises like Civilization and Hearts of Iron have always had huge followings, I always assumed that strategy game fans were a small, insular group devoted to chewing over a few massive, heavyweight classics for years on end. I would never imagine that they would be interested in the hectic and ever-changing indie game scene.

Enter Hooded Horse, a U.S.-based publisher known for recent strategy indie games such as Manor Lords, 9 Kings, and Against the Storm. With each new early-access and full release, Hooded Horse has pulled in several positive reviews, proving that the demand for strategy games is alive and stronger than ever.

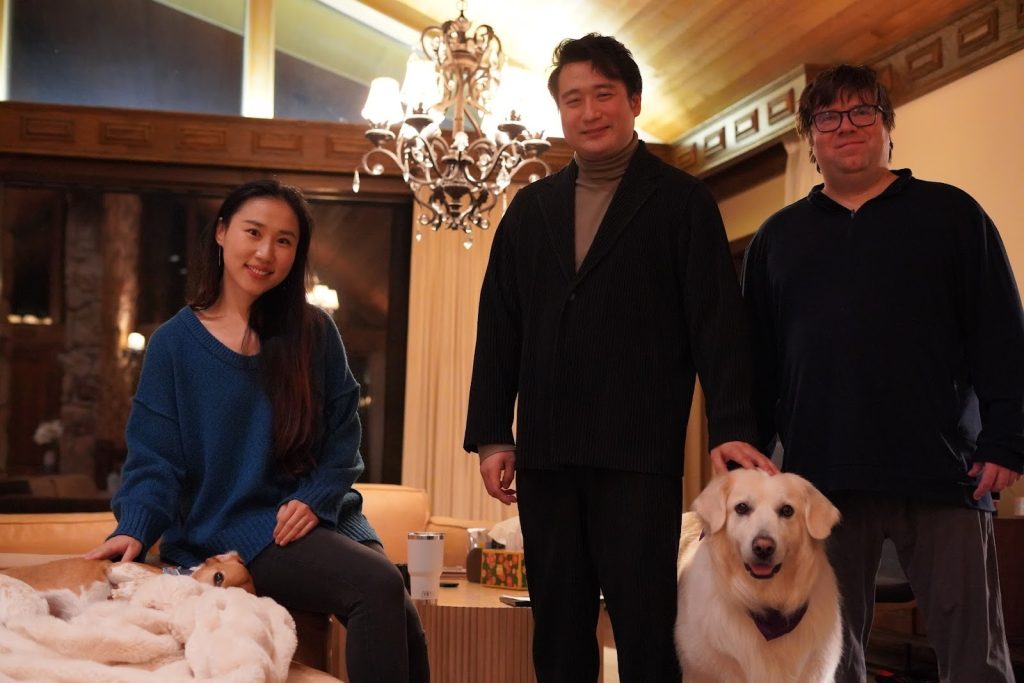

But how did this rising publishing company get started, and where is it headed? Why did Hooded Horse decide to focus solely on strategy games, and is it possible to survive on a single genre alone? Last November 2024, I.N.T. flew to Seattle to talk to CEO Tim Bender and CFO Snow Rui, and find out more about what’s under the hood of this particular horse.

(The couple’s dogs greeted us warmly at their home.)

Editor / Jini

Interviewer / Daichi Saito

Interpreter / J-mon

Photographer / Author / Shu Chiba

Saito:

I’m Daichi Saito, a producer at I.N.T. and head of the indie publisher WSS Playground. Today, I’ll be speaking not only as a game journalist but also as a publisher – one who has staked his own label on “character-driven games.” I’d like to delve into the secrets behind the enigmatic Hooded Horse.

Tim:

I’m Tim Bender, CEO of Hooded Horse. Thank you for coming all the way from Japan.

Snow:

And I’m Snow Rui, COO and CFO. A pleasure to be here.

Saito:

I normally begin by asking, “Why did you choose to become a publisher focused on strategy and RPG titles?” While this is something I’m very curious about as a fellow publisher, let me start with this instead:

“What do you think makes strategy games so wonderful? Why do you love them?”

Tim:

The beauty of strategy games is the challenge that comes with them.

A strategy game demands constant thought. It presents you with fresh challenges, intriguing choices, and forces you to live with the consequences. In a sense, it’s a cycle of hypothesizing, testing, and drawing conclusions.

Every option comes with trade-offs; there is no single “best” answer. Even the path that seems “better” is shaped by an interplay of countless variables that constantly shift the situation. To wrestle with that chaos and gamble on choices – that is the essence of strategy games.

The harder the challenge, the better. It is only when you’re forced into difficult, painful decisions do your choices truly leave their mark. That is where the core experience of strategy games lies.

Saito:

That’s quite a hardcore answer. Let’s talk about your background, then. What was the very first game you played?

Tim:

Civilization (1991). The very first game in the series.

(The inaugural title in the legendary Civilization series.)

Saito:

So you were a strategy fan from the very beginning!

Tim:

You could say so. Although the real story is less poetic.

When I was six, my mother said my sister and I could pick just one game between us when we went shopping. My sister chose Civilization. I wanted Quest for Glory: So You Want to Be a Hero (1989), which is an adventure RPG. But how could a scrawny kid stand up to his big sister?

So I ended up playing Civilization. For a six-year-old, the game was utterly incomprehensible. I didn’t even know how to change the units I was producing, so I churned out the weakest troops and wandered around a tiny island until I was crushed by enemy carriers and tanks.

It was a miserable first experience, but I found myself drawn to the game’s cycle of defeat and learning from my mistakes. I dove headfirst into strategy games, picking up anything that resembled Civilization. As I grew older, I began to understand the systems better. The more I understood, the more fun it became.

There’s an epilogue to my story. A month later, I begged my mother to get me Quest for Glory and she relented. Because of that, I became an RPG fan as well.

(Sierra On-Line’s beloved adventure-RPG series, Quest for Glory.)

Tim:

Perhaps Hooded Horse owes its existence to my sister. Without her, I might have never touched Civilization.

The rest of my childhood was spent buried in games. It was also the dawn of the MMORPG era, so I played everything I could get my hands on. Ultima Online (1997), with its chaotic freedom, was unforgettable. It’s a shame so much of that chaos has disappeared from today’s MMOs.

Saito:

If you had to pick just one favorite game of all time, what would it be?

Tim:

For strategy, XCOM: Enemy Unknown (2012). Its combat design was revolutionary. The movement system, the interplay of skills and mechanics – everything was so clean and elegant. It was a smart, modern reinvention that completely redefined the genre. Credit to Jake Solomon’s genius.

For RPGs, probably The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind (2002). I first played it when I was eighteen years old, and what struck me was how much of the game’s systems you had to figure out for yourself. There were no quest markers back then. You had to think, explore, and carve out your own experience. That’s what made its world so beautiful. Of course, I also modded Morrowind heavily, so I can’t remember what the vanilla game is like.

(XCOM: Enemy Unknown was developed by Firaxis, who are also the creators of the Civilization series.)

Saito:

I heard that you were deeply into modding. For many players, enhancing game experiences with mods seems natural. For us in Japan, however, the dominance of the console market means that the country’s modding scene never really took off.

Tim:

Mods are a way to expand a game’s possibilities. I have been captivated by the idea since childhood.

Take Civilization, for example. By default, it’s grounded in real history, but with mods, it could be turned into a fantasy setting. I love reading fantasy. The Shannara Chronicles is a personal favorite, as is J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. So when I found a Civilization II (1996) scenario based on The Silmarillion, I installed it immediately.

(A fan-made scenario for Civilization II based on The Silmarillion: “Dagor Bragollach.”)

Tim:

It was brilliant. In Tolkien’s story, the elves are crushed in that battle. The mod recreated it and challenged you to see if you could avert that doom. Winning didn’t mean defeating the enemy; it meant avoiding total catastrophe. Fighting for survival against impossible odds was thrilling.

Later, I devoured Civilization IV’s “Fall from Heaven” fantasy mod. XCOM: Enemy Unknown’s “Long War” mod left a deep impression on me as well.

Saito:

Did you make any mods yourself?

Tim:

Plenty, though they were usually just for personal use. The only one I ever released publicly was for Mount & Blade: Warband – Viking Conquest (2010).

I mostly made difficulty mods because I like handicapping myself. For instance, even though Long War was already tough, I felt it was too easy. So I made a mod that halved tech progression speed and boosted enemy HP.

Snow:

Tim got me into playing Mount & Blade as well, and I really enjoyed it. I’ve always had a deep interest in Viking culture. I even went on archaeological digs in Scandinavia. Naturally, the Viking Conquest expansion became a favorite of mine.

Tim’s mod for the game started as just a set of small balance tweaks, which is why he called it the “Balance Mod”. But it quickly grew in scope. As an example, Tim measured the marching speed of armies on the game map and compared it against actual historical records. Then he rescaled the entire map so that travel times would be historically accurate. As a result, marching across the map took about twice as long as before.

That’s what it’s like playing with him. He always wants the hardest difficulty possible.

Tim:

I’m always chasing that thrill. In almost every game, I want something tougher than the hardest difficulty.

(Tim’s “Balance Mod” for Mount & Blade: Viking Conquest.)

Saito:

When did you work on the Mount & Blade mod?

Tim:

Between 2015 and 2018. I was in New Haven at the time and had several spare hours to work on modding the game. Once you start adjusting things, you find more and more things that need changing. I overhauled the upgrade trees, too

By 2018, I’d finished grad school. Snow was working as a lawyer, so we could afford it. Then a close friend came along, who was a law school classmate. He’d done well for himself, had money to invest, and was always looking for opportunities. When he saw how much fun I was having with mods, he said: “If it’s that fun, why not make it your job? I’ll invest.”

And that’s how Hooded Horse began.

Saito:

I’d love to get to the founding story, but let’s go back further first. You studied at the University of Texas at Austin, correct?

Tim:

Yes. At university, I focused on academics and had only just one or two hours a day for gaming.

I started as a math major. But after trying a law school practice exam and scoring extremely well, I realized law was just as logical and structured as math. That appealed to me, so I set my sights on law.

I was impatient. I realized that if I doubled my course load for a year, I could graduate early. So I took 2.5 times the usual credits, finished in two years, and headed for law school.

Saito:

Two and a half times the credits? How did you even attend all those classes?

Tim:

I didn’t. For some, I just skipped lectures and only took the exams. With enough study, I passed.

Saito:

From there, you went to Stanford Law, became a lawyer, and then left after a year. You moved to Harvard for East Asian politics, then McKinsey as a consultant, then Harvard again for a master’s in Chinese history. Why abandon such prestigious careers?

Tim:

Because neither law nor consulting felt like they were making the world better.

Sure, I learned valuable skills, but I didn’t enjoy it. I’d rather spend my life studying history, which is something I love.

Academics broadened my horizons. I‘ve always loved European history, but East Asian history gave me a wider perspective on the world. And, of course, it’s where I met Snow.

Snow:

We met in a seminar on Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian. Just six students and one professor. Two of those six pairs later married—including us! We used to joke it was less a seminar and more a marriage bureau.

Saito:

So after law, consulting, and multiple degrees, your friend encouraged you to go into publishing. Did you really believe that game publishing could make the world better?

Tim:

At first, I hoped so. After five years, I’m convinced. Indie game publishing can make the world better.

It gives creativity a chance. It amplifies new artistic voices. It creates paths for good work to emerge. When I look around at the people enjoying games and see our titles among them, I feel proud. Unlike my other careers, I can say that the harder I work in game publishing, the better the world becomes.

Saito:

I’ve interviewed developers all over the world, and many of them share that same belief. I also think indie publishing is a force for good.

Saito:

Let’s circle back to the original question: Why did you decide to focus exclusively on strategy and RPG publishing?

Tim:

That wasn’t the original plan. While I’ve always loved strategy games and RPGs and wanted to work with them in some capacity, I didn’t decide to build a label entirely around them.

Upon founding Hooded Horse, the first studio I reached out to was Pavonis Interactive, the studio behind XCOM: Enemy Unknown’s Long War mod. Back then, they were working on what would become Terra Invicta. After that came Falling Frontier and Old World, the latter of which was designed by none other than Soren Johnson, the lead designer of Civilization IV and Spore (he is one of my personal heroes).

Step by step, I signed more strategy projects. As Snow and I studied the market, we realized that my personal taste in games and the business logic aligned perfectly. It wasn’t a grand plan, more so a natural evolution. That’s how we became a publisher that specializes in strategy games and RPGs.

(Terra Invicta, one of Hooded Horse’s earliest contracts.)

Saito:

It was a smart choice. Strategy games typically have a large audience, but are few and far between.

Tim:

Yes, but people sometimes draw the wrong conclusion. They say that strategy games are an easy way to make money, but that’s not true. Developing a strategy game requires a larger team and a longer timeline than other genres, often taking four to five years, sometimes longer if early access is involved. That alone makes it very different from other indie genres.

In addition, many well-funded, well-reviewed strategy titles have sold fewer than 10,000 copies. I once saw a dozen strategy games, each with a million-dollar budget, vanish without a trace. That’s the harsh reality. So no. It’s not “easy.”

(Hooded Horse’s growing lineup of strategy hits.)

Tim:

What makes strategy games uniquely hard is the extremely high standards that players have. Strategy fans know the genre inside and out. Their critical eye is sharp and merciless, so meeting their expectations is no small feat.

If the difficulty is too easy, they’ll call it “worthless.” They also want their games to be of adequate length. If a game ends (or worse, grows stale) after 20 hours, they’ll complain that it’s too short.

Saito:

Tell me about your relationship with your partner developers. How do you choose who to sign with?

Tim:

We look for uniqueness in their games – something that players can fall in love with. Especially with the strategy genre, the key is whether the game’s special spark will resonate with fans.

We pass on projects when the scope and budget don’t align with the potential audience. If the target is too niche, we can’t promise success to the devs.

Saito:

Do you always invest during the early stages of development?

Tim:

It depends. Broadly, there are two types of developers we work with.

The first type of partners includes teams that can fully self-fund their projects, often because they’ve already had a few successful titles under their belt. Overhype Studios, creators of Battle Brothers, didn’t need our money for their new game, Menace. In their case, we provided pure publishing support.

The second type of partners are teams that need investment. For them, we provide partial funding and take a larger revenue share.There are exceptions. In the case of Mohawk Games and their most recent title, Old World, the studio had lost its previous publisher. Since the game was nearly finished and already in early access, Hooded Horse stepped in post-release and handled the publishing without having to fund its development.

(Old World—initially self-published, later re-released with Hooded Horse as publisher.)

Saito:

How much do you get involved in design itself? Do you advise on concepts?

Tim:

We only sign games when the developers are deeply convinced of their concept. We don’t choose based on “what might sell.” We choose based on “what the creators love.”

So, we don’t interfere at the concept stage.

Saito:

Then what do you advise on as a publisher?

Tim:

Mostly scheduling. Our Chief Product Officer, Ashkan Namousi, works closely with teams to help structure development timelines. This is especially true for smaller studios, which often lack the capacity to plan thoroughly.

We also provide feedback. Our Player Experience Director, Mandalore (a well-known YouTuber), talks with devs regularly, offering detailed advice by asking questions like “Is this voice actor right?” and “Is the difficulty tuned properly?”

Sometimes, we even loan out our in-house artists or UI designers to teams, and they get credited in the games.

Outside of development, we handle localization, multi-platform management, payments, PR, and store coordination.

Saito:

What about developer-to-developer communication?

Tim:

We gather them all in a Slack workspace. They’re incredibly active at sharing technical advice, gameplay ideas, and lots of pet photos.For example, when Manor Lords’ developer Slavic Magic hesitated to build a non-Steam version of its game, Minakata Dynamics, the studio behind Whiskerwood, volunteered to help. That spirit of mutual aid is common amongst our partner studios.

(Thanks to that help, Manor Lords also launched on Epic Games Store.)

Saito:

That’s wonderful. It’s not easy to support creators while keeping them independent.

Tim:

Independence matters. For sustainability, devs need financial breathing room. That’s what leads to creative freedom and a future.

That’s why Hooded Horse doesn’t do recoup.

Saito:

For clarity: “recoup” means the publisher recovers its investment before developers see any revenue, right? Like if you invest $100,000, every dollar of revenue goes to the publisher until that $100k is repaid.

Tim:

Exactly. That tradition traps devs. With a recoup in effect, the developers will sometimes walk away with nothing even after years of work. They then scramble for survival jobs and may never recover.We want to free them from that cycle.

Most devs just want to create something original. They don’t want to churn out clones or build upon existing ideas. Our mission is to help them chase their passions. That’s why we build dev communities too.

Saito:

What about Hooded Horse itself? The company has close to 30 staff now, all of whom are working remotely. How do you manage them?

Snow:

We try to keep communication frequent. Everyone has their own work pace, so team leaders coordinate meeting times and workflows according to that. Every employee is a professional with their own specialty, carrying heavy responsibility but also wide autonomy.

They don’t need our constant approval. Nor do we expect it. Without that trust, a small company like ours could never handle this many publishing projects.

Saito:

One unique thing about Hooded Horse is the presence of streamer employees. For example, you have on your marketing team PartyElite, a YouTuber. You also mentioned Mandalore earlier. How many streamers are actually on staff?

Tim:

About eight. They’re active on YouTube or Twitch, and they understand players deeply. That makes them invaluable for understanding marketing, especially since strategy players are analytical. Having staff who “speak for the fans” is crucial. However, note that we never involve their streamer role with their marketing for us – if they choose to cover our games it’s entirely separate from their work for Hooded Horse.

(Mandalore, a popular YouTuber with 900,000+ subscribers, also serves as Hooded Horse’s Player Experience Director.)

Saito:

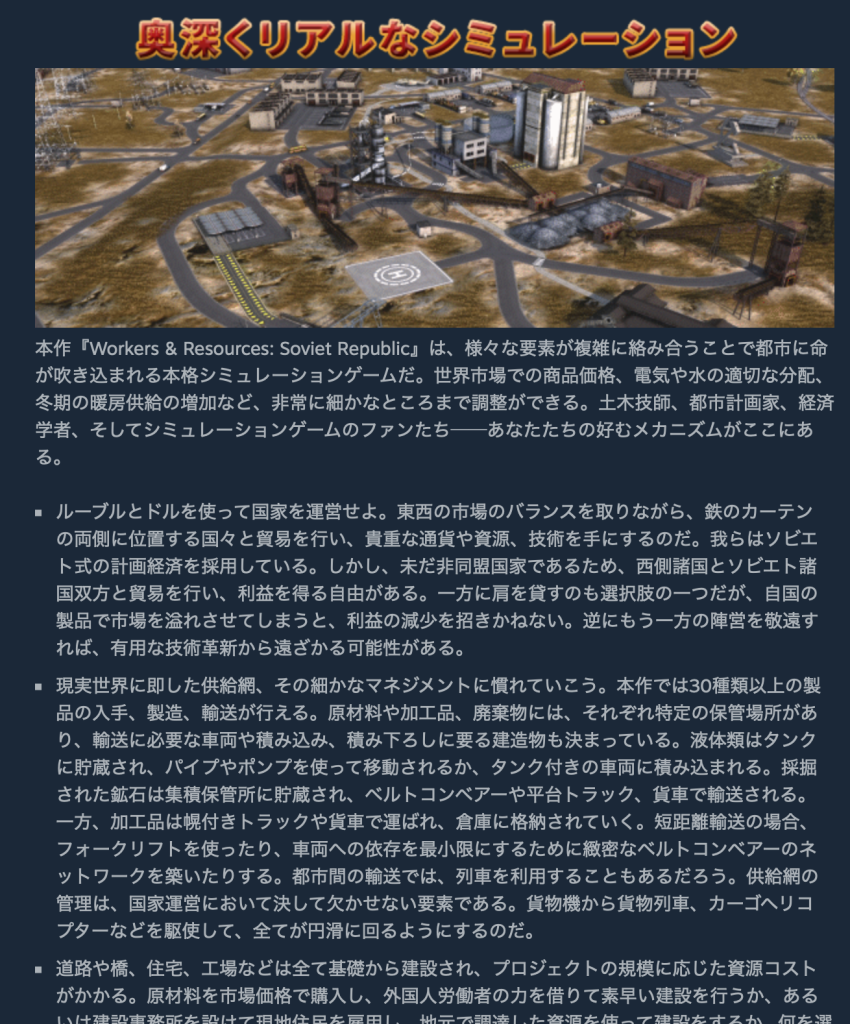

Your Steam store pages are incredibly detailed and compelling.

Tim:

That’s intentional. The greatest marketing strategy is communicating a game’s true appeal.

We fill our Steam pages with extensive descriptions, and our trailers showcase real gameplay and UI elements. It isn’t flashy, but it is exactly what our target players want. They don’t need cinematic hype or meme marketing. They want a game’s promises to be clearly stated, and they want those promises kept. That trust, built with every game we publish, is our real advertising.

(The Steam page for Workers & Resources: Soviet Republic—its description stretches for multiple scrolls.)

Saito:

But what about social media?

Tim:

Social media is for deepening engagement with what you already know, not for discovering new things. We prefer store platforms, YouTube, Twitch, and game media, both online and offline.

We don’t spam game codes when approaching influencers. We keep a detailed list of influencers and only target those fluent in strategy games who can really evaluate a title.

Saito:

Your official tagline is “Publisher Inspired by Strategy, Simulation, and Role-Playing Games.” “Strategy” and “simulation” make sense because the words are close cousins. But from a Japanese perspective, adding “RPGs” to your tagline feels unusual.

Tim:

They’re not so distant. Both strategy and RPGs revolve around choices and consequences – narrative transitions shaped by decisions. Their fanbases overlap as well. By appealing to that intersection, we built recognition.

Of course, not everyone plays these genres. Someone might love Xenonauts 2’s tactical RPG combat but not Capital Command’s spacefaring sandbox simulation gameplay. Still, there is a chance for cross-pollination.

The key is not to lock ourselves into one narrow direction. If a player says, “I like 70% of Hooded Horse games but not 30%,” that’s a victory. But we must stay mindful of what defines us. One recurring trait of our games is difficulty. Not cruelty for its own sake, but the possibility of game over.

Games that are designed only to comfort players, no matter how strategic, aren’t for us.

Saito:

Speaking of genre trends, roguelike elements get added to everything these days. What do you think of that?

Tim:

I don’t consider “roguelike” a genre, at least not in the modern, catch-all sense.I love traditional roguelikes like Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup (2006) and NetHack (1987). That lineage forms a coherent taste.But players of classical roguelikes and players of modern “roguelites” like The Binding of Isaac have no connection. Genre is defined by its audience. Because roguelike elements are so modular, they don’t unify a community. While they can flavor individual games, they don’t bind players together. Under those circumstances, it’s very difficult to treat it as a coherent genre.

(Tim cites Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup and NetHack as “true roguelikes.”)

Saito:

Indeed, if there were a roguelike-only publisher, its catalog would end up becoming incoherent. Fans wouldn’t stick around.

Tim:

Exactly. If you want to build a publisher defined by a particular genre or aesthetic, you need to base it on traits that carry meaning for a shared audience. That’s what allows you to form a real fan base. It’s not about the publisher and players being identical. It’s about players sharing common needs that the publisher can serve.

Snow:

Let me give an example outside of games. Imagine you were the owner of an oil company sixty years ago. Would you define yourself as “a company that makes oil and gasoline”? Or as “a company that provides energy”?

The former defines you by your product; the latter defines you by the needs you fulfill. If you define yourself as “an energy company,” then later you can move into wind power or solar power, adapting flexibly as times change.

But if you lock yourself into “we’re an oil company,” then alternative energy sources fall out of sight. Defining yourself only by your product is dangerous.

Saito:

Aside from Hooded Horse, are there other indie publishers that have managed to focus on a specific genre, taste, or theme and really make it their identity?

Tim:

Fellow Traveller and New Blood Interactive.

Fellow Traveller has firmly positioned itself as a narrative-game publisher, building a distinct audience that isn’t easily defined by genre labels. New Blood, meanwhile, has carved out a retro-horror aesthetic with a strong following.

Both are consistent. Their publishing catalogs align with their identities, and they reliably deliver what their fans expect. That’s the strength of having a publisher identity built on a particular trait.

Take horror, for instance. There are many subgenres of horror games, but horror fans aren’t strictly divided by subgenres. A single horror fan often enjoys multiple different strands. That overlap has given rise to the diversity of today’s horror publishers. If you wanted to become a publisher now, horror might actually be a promising niche to specialize in.

(New Blood Interactive’s lineup includes distinctive horror titles such as FAITH: The Unholy Trinity and DUSK.)

Saito:

I feel the same about Fellow Traveller, where I see a clear throughline in its work. But beyond you three – Hooded Horse, Fellow Traveller, and New Blood – I can’t think of many publishers that specialize in a particular game genre.

Tim:

That’s because most publishers prefer to go broader. It’s easier to widen your options and take on all sorts of projects.

If you choose to specialize, the range of titles you can accept narrows drastically. We get pitches for all kinds of games, and sometimes we see ones we personally love. But if they don’t fit the Hooded Horse identity, we can’t publish them. In those cases, we have to turn them down and sometimes point them toward other publishers. Maintaining consistency is hard.

Saito:

That’s why restraint is considered a virtue. I’ve seen publishers who once had strong identities lose them over time by chasing too many opportunities. When good projects come your way, the temptation to say “yes” is strong. The more successful a publisher becomes, the more temptations come its way, making it harder to preserve its original color.

In my case, I rarely take outside pitches. I only greenlight projects that start from my own offers, right from the concept stage. It’s the opposite of your approach, but that’s how I maintain consistency for our label.

Tim:

That’s a very reasonable method.

Saito:

From the outside, Hooded Horse looks very stable. If you wanted, you could triple your staff and aim to rival Paradox. Why not?

Tim:

Because indie publishers do better by not over-expanding.

Our current size is sustainable and functions smoothly, with everyone an expert in their field. When we first started, we struggled to find devs. Now, talented teams bring pitches to us. We have skilled staff, trusted press contacts, and loyal fans. Everything has gotten easier with time.

Why break that stability? Growth for its own sake creates risks and distractions. We don’t need it.

Saito:

You were a modder yourself. Will Hooded Horse ever move into internal game development?Tim:

No. Making games requires very different skills and staffing. You can’t do it on the side. If I ever did it, it would be with a completely separate studio. Hooded Horse will stay a publisher.

There might come a time when I want to create a game myself. If that happens, I wouldn’t do it through Hooded Horse. I would set up a completely separate studio as a developer. I’d also hire an entirely different group of staff. Different fields require different people. It would be absurd to expect the staff at a grocery store to suddenly start running a farm as well.

Saito:

That made me think of an analogy. In Civilization, there are not only conquest victories, but also cultural and religious victories, right? So if expansion and growth aren’t your win conditions, what is?

Tim:

In Civilization, I never cared about win conditions. Even after “winning,” I’d keep playing by running the world and keeping it stable.

That’s my answer. Our victory is simply continuing. Not growth, but longevity. If Hooded Horse still thrives 100 or 200 years from now, that’s success.

Saito:

But as a gamer, you always sought to increase the maximum difficulty. Isn’t the company too easy to manage now?

Tim:

That’s the difference between games and life. In games, I chase thrills. In life, I seek stability. My challenge now is making each of our publishing projects succeed. Even as life becomes more stable, mystery and curiosity never run out – nor does the sense of surprise that new games provide. For devs, a release is a once-in-five-year event. For publishers, it’s routine. But that routine is filled with learning.

Starting Hooded Horse was a challenge worthy of strategy gamers such as ourselves. Because we refused to take money from institutional investors to remain independent, our financial resources were limited, and survival was uncertain. It’s a good memory now, but it’s not something I would ever want to do again.

The challenge that excites me today is successfully publishing a game.

Saito:

You said indie publishing makes the world better. With today’s uncertainty, will that still hold true?

Tim:

Yes, because indie games always explore new paths. Big-budget games, which are often burdened by risk and timelines, usually stick to sequels and clones. But indies can take chances. They can survive on 100,000 sales, explore niche ideas, spread happiness, and invent new genres.

There is a magic to indie developers, and our role as publishers is to help make that magic possible.

Despite being presented with several paths that could have led to a safe and successful career, Tim Bender instead chose to found an indie publisher specializing in strategy games and RPGs. Hooded Horse would go on to publish several indie titles, bringing the joy of the genre to players around the world. In a triple-A industry filled with safe choices, Hooded Horse endeavors to bring new ideas to life.